Let’s not forget that the the leading modernists T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound called for a satirist to describe the changes of the early twentieth century. (Eliot wanted someone like Alexander Pope, the subject of my last post.)

Despite his name, Evelyn Waugh was their man. He denied that he wrote satire, but his cheeky and fiendish early novels fit perfectly in the tradition of Dryden, Swift, and Pope. His sleek prose style, along with that of P.G. Wodehouse, remains the gold standard of English comedy writing.

Although he had a taste for country house society, he was hip to the developing modernity he would come to deplore. He was one of the first to understand the force of Eliot’s poetry, using lines from The Waste Land for the title of one of his novels (A Handful of Dust) and for a section of another (Brideshead Revisited).

Yet, something about the fast-changing modern world disheartened him. In 1930, after his first marriage failed, he converted to Catholicism, but even that source of stability failed him after it enacted a series of reforms known as the Second Vatican Council. Upon Winston Churchill’s election victory in 1951, he complained that “the Conservative Party have never put the clock back a single second.”

But beware those who claim that Waugh isn’t worth reading because of his unabashed snobbery — they are blinded by a prejudice of their own. Even people with different political positions can find many valuable things in his work. (While a student at Cambridge, I was friends with a loyal Jeremy Corbyn supporter who could quote passages from Brideshead Revisited by heart.) You could say that Waugh was a traditionalist, but you could also say that he wrote as well as he did precisely because he hated the modern world. He wasn’t a mere reactionary propagandist: his novels are still widely read and loved, proving that there’s more to being a good novelist than having progressive political opinions.

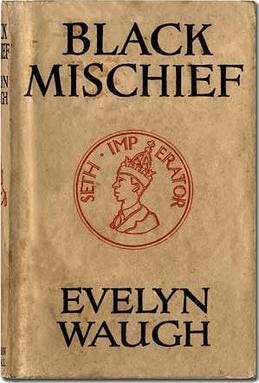

Waugh’s novel Black Mischief, which turns 90 this month, is a mordant satire of progress and fashionable beliefs. Its welter of plots isn’t easy to summarise, but, broadly speaking, the novel is based on the old comedic idea of a “clash of cultures.”

The Oxford-educated Seth becomes Emperor of Azania, a fictional island home to a mix of racial and religious groups. Aided by his fellow Oxonian Basil Seal, Seth tries to modernise Azania in the name of “Progress,” by introducing modern amenities such as railroads, Montessori schools, and birth control. These schemes fail and anarchy erupts. Seth and his rival to the throne are both killed. At Seth’s funeral feast, Basil unknowingly eats a stew made from the remains of his girlfriend Prudence (the pampered daughter of a British minister) whose evacuation plane crashed in the jungle. Back home in London, Basil recounts his experiences to his friends, who now find him boring.

Yes, this is a comedy.

The combination of the funny and the feral is a distinguishing quality of Waugh’s novels, but some readers failed to see the value in it. In January 1933, the editor of the Catholic weekly The Tablet, Father Earnest Oldmeadow, wrote:

Whether Mr. Waugh still considers himself a Catholic, The Tablet does not know; but in case he is so regarded by booksellers, librarians, and novel-readers in general, we hereby state that his latest novel would be a disgrace to anyone professing the Catholic name. We refuse to print its title or to mention its publishers.

It’s unsurprising that a Catholic priest disliked a story featuring cannibalism and contraception, but it is surprising that Father Oldmeadow completely missed the point of the novel, which is to mock immoral actions, especially those of the British governing class.

I don’t want to impugn the reading skills of Father Oldmeadow, but the novel’s opening paragraph makes it fairly clear what sort of story the reader can expect:

“We, Seth, Emperor of Azania, Chief of the Chiefs of Sakuyu, Lord of Wanda and Tyrant of the Seas, Bachelor of the Arts of Oxford University, being in this the twenty-forth year of our life, summoned by the wisdom of Almighty God and the unanimous voice of our people to the throne of our ancestors, do hereby proclaim…” Seth paused in his dictation and gazed out across the harbour where in the fresh breeze of the early morning the last dhow was setting sail for the open sea. “Rats,” he said; “stinking curs. They are all running away.”

Emperor Seth’s pompous speech is undercut by the reference to his degree among his other titles, and then by the interruption of the narrator who tells us that “the last dhow” is carrying escapees from Azania. It’s slightly amusing that Father Oldmeadow misread Black Mischief in such a way, as the novel itself features a misreading of its own.

The link to Oxford University reminds the reader that Emperor Seth wants to bring enlightened, modern ideas to Azania. He resorts to “the power of advertisement” to teach his illiterate Azanian subjects “the benefits of birth control.” “We must popularise it by propaganda — educate the people in sterility,” he tells Basil.

Seth circulates a “large, highly coloured poster” that portrays two contrasting scenes:

On one side a native hut of hideous squalor, overrun with children of every age, suffering from every physical incapacity — crippled, deformed, blind, spotted and insane; the father prematurely aged with paternity squatted by an empty cook-pot; through the door could be seen his wife, withered and bowed with child bearing, desperately hoeing at their inadequate crop. On the other side a bright parlour furnished with chairs and table; the mother, young and beautiful, sat at her ease eating a huge slice of raw meat; her husband smoked a long Arab hubble-bubble (still a caste mark of leisure throughout the land), while a single, healthy child sat between them reading a newspaper. Inset between the two pictures was a detailed drawing of some up-to-date contraceptive apparatus and the words in Sakuyu: WHICH HOME DO YOU CHOOSE?

As in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (published in the same year), contraception is a symbol for the sterility of the modern, technocratic world and its spiritual decay. Waugh brilliantly derides the administrative classes and the presumptive imposition of their ideas onto others. The narrator remarks: “nowhere was there any doubt about the meaning of the beautiful new pictures,” and then assumes the perspective and voice of a native Azanian:

See: on right hand: there is rich man: smoke pipe like big chief: but his wife she no good: sit eating meat: and rich man no good: he only one son.

See: on left hand: poor man: not much to eat: but his wife she very good, work hard in field: man he good too: eleven children: one very mad, very holy.

To the populace, it’s the family rich in children that seems blessed compared to the one lost in material comforts; they think Seth’s birth control apparatus is a fertility charm, the “Emperor’s juju.”

For the rulers of Azania, however, it’s contraception that is sacred. Seth renames the Anglican cathedral “Place Marie Stopes,” after the English campaigner for birth control and eugenics. He launches the Birth Control Parade, in which schoolgirls flaunt banners with the mottos “WOMEN OF TO-MORROW DEMAND AN EMPTY CRADLE” and “THROUGH STERILITY TO CULTURE.” This Mardi Gras of infertility remains incomplete as riots break out. The symbolic banner is so badly crumpled that only the word “STERILITY” remains legible.

Seth seeks to modernise Azania, but all he can bring from the cleverest part of the modern world (Oxford University) is a fake religion that worships gadgets and nullity. Waugh satirises the cult of material progress and the secular world’s urge to invent rituals, however ridiculous. Equally despicable is the propaganda of the enlightened magnates, who can’t even organise a successful parade, let alone a flourishing country.

The comedy of Black Mischief depends on the failures of imposing twentieth-century English ideals onto a society that isn’t suited to them. Moreover, Waugh’s novel depicts the distinctly modern form of boredom that results from secularisation and solitude — in the narrator’s words, the “acquired loneliness of civilisation.” It’s a sort of sophisticated boredom, a refusal to be shocked or moved or impressed on the pretense that everything is beneath you. Waugh captures this perfectly in the dialogue between the inaptly-named Prudence and the aptly-named William Bland. This is meant to be pillow talk but they are clearly not sharing a cosy moment:

“I’ve invented a new way of kissing. You do it with your eye-lashes.”

“I’ve known that for years. It’s called a butterfly kiss.”

“Well, you needn’t be so high up about it. I only do these things for your benefit.”

“It was very nice, darling. I only said it wasn’t very new.”

“I don’t believe you liked it at all.”

“It was so like the stinging thing.”

“Oh, how maddening it is to have no one to make love to except you.”

“Sophisticated voice.”

“That’s not sophisticated. It’s my gramophone voice. My sophisticated voice is quite different. It’s like this.”

“I call that American.”

“Shall I do my vibrant-with-passion voice?”

“No.”

“Oh, dear, men are hard to keep amused.” Prudence sat up and lit a cigarette. “I think you’re effeminate and undersexed,” she said, “and I hate you.”

“That’s because you’re too young to arouse serious emotion.”

This is the blasé attitude of a generation that, hyper-stimulated and burned-out by a machine-led society, can’t even get excited about sex. Subject to the mechanical, meaningless routines of the modern world, Waugh’s characters don’t even yearn for the beautiful and transcendent. György Lukács (usually not very insightful) called this feeling “transcendental homelessness,” and Basil tries to find meaning by participating in a significant historical event in Azania, a foreign country yet to be corrupted by these modernising ideals.

This deadpan, unaffected style, however, creates some of Waugh’s greatest comic moments. Another target of his is the type of person who hides callousness under compassion. The animal rights activists Mildred Porch and Sarah Tin profess a great solicitude for the welfare of animals while treating everyone they meet with disrespect. Here are a few examples from Mildred's diary:

Disembarked Matodi 12.45. Quaint and smelly. Conditions of dogs and horses appalling, also children.

Saw Roman ministry. Unhelpful. Typical dago attitude towards animals.

Fed doggies in market place. Children tried to take food from doggies. Greedy little wretches.

Waugh was the master of introducing a gruesome detail in an understatement. The novel starts with a war between Seth and Seyid, but the reader doesn’t learn Seyid’s true identity until about page 57. The timing is delicious. Comics, take note. Here’s the exchange between Seth and General Connolly:

“And the usurper Seyid, did he surrender?”

“Yes, he surrendered all right. But, look here, Seth, I hope you aren’t going to mind about this, but you see how it was, well, you see Seyid surrendered and…”

“You don’t mean you’ve let him escape?”

“Oh, no, nothing like that, but the fact is, he surrendered to a party of Wanda… and, well, you know what the Wanda are…”

“You mean…”

“Yes, I’m afraid so. I wouldn’t have had it happen for anything. I didn’t hear about it until afterwards.”

“They should not have eaten him — after all, he was my father…”

Waugh’s cool, emotionless prose highlights the insensitivity of people like Seth and Mildred Porch, the cruelty of a modern society towards its parents and children.

Black Mischief contrasts two types of people: those who, like Seth, have too many ideas and try to impose them on a population that isn’t interested; and those who, like Prudence, lack any thought and are entirely preoccupied with material pleasures. Waugh’s novel skewers the pretentions of the modern world. Not only does it expose the futility of Seth’s ambitions, but it shows that the modern civilisation he wants to introduce is worthless, materialistic, and boring.

Waugh might have been a curmudgeon in tweed, but few novelists better described the important trends of the first half of the twentieth century, and no one was funnier while doing so. Whatever your politics, I think you can agree that something went very wrong in 1914: the most “advanced” technology was used to turn a generation of young men into corpses on muddy fields; the most “advanced” countries used their assets to further their violence and barbarism; the most “advanced” techniques of media and communication were used for demagoguery and propaganda.

It’s these developments, and the societies they created, that gave Waugh his material. He noted the incredibly dynamic element of modernism, and his rejection of it created the brilliant tension of his writing. In his acerbic prose, he derided a society lost in gizmos, a society led by incompetent megalomaniacs, a society that considers childbirth dowdy and undignified.

Finding even the Catholic Church too modish, Evelyn Waugh hated “progress,” — but 90 years after the publication of Black Mischief, what has changed?

This is an excellent introduction to the novel, which is in my view easily the equal of others in the modern dystopia genre such as 1984. I recently reread it and was struck by Waugh's inclusion of Vaccination as an important element in the modernising agenda. Also Seth's decision to print money to finance his progressive plans foreshadows the so-called quantitive easing, i.e. disastrous money printing by western governments in the last 15 years. We are all living in Seth's Azania now.

Well written, my friend. And interesting. The title of your post for this is perfect. My favorite point made: ‘You could say that Waugh was a traditionalist, but you could also say that he wrote as well as he did precisely because he hated the modern world. He wasn’t a mere reactionary propagandist: his novels are still widely read and loved, proving that there’s more to being a good novelist than having progressive political opinions.’

Boom.

Michael Mohr

‘Sincere American Writing’

https://michaelmohr.substack.com/