Despite being a clumsy novel in some places, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has grown to become a myth. By “myth,” I don’t mean a story that might have some historical elements mixed with fiction or a silly fable to entertain children; a “myth” is something that symbolises how humans behave and interact.

A hint that Frankenstein is a myth comes from its subtitle: “A Modern Prometheus.” Who, then, is the modern Prometheus? The obvious answer is Victor Frankenstein. He wants to improve mankind, defies a divinely established order, and harnesses a natural force (electricity) to create a living being. Like Prometheus, Frankenstein dooms those he was trying to help.

Paul Cantor, however, argues that the creature also has Promethean qualities: he is the one who “discovers” fire and becomes the lonely, tortured victim. As the novel progresses, though, it becomes increasingly hard to distinguish Frankenstein and his creation, which is partly why people often refer to the creature as “Frankenstein” even though this is the name of his creator.

Considering the similarities between Frankenstein and the creature helps the reader to see other mythical elements of Mary Shelley’s novel. There are things humans need to have and things humans need to be. A list of things you need to have might include:

Food

Water

Shelter

A list of things you need to be might include:

Maturity

Society

Wisdom

Frankenstein shows us two men (Frankenstein and his creature) who have everything from the first list but almost nothing from the second. Frankenstein has a harmonious childhood with loving parents and affectionate friends, but his “predilection” for natural philosophy ruins it. He discovers a volume of Cornelius Agrippa’s “chimerical” theories, and “Chance—or rather the evil influence, the Angel of Destruction,” leads him to M. Waldman, who encourages his study of the “dreams of forgotten alchemists.”

Frankenstein craves knowledge but has no reliable guide; his obsession weakens his cultural and social links, which he destroys completely when he defiles the dead in pursuit of his goal. (A society that doesn’t respect its dead exposes everything to pillage.)

In a novel unlike anything expressed in the work of her husband Percy Shelley, Mary Shelley shows that desire is egotistical and destructive. It doesn’t lead to insight or innovation and is ruinous to mankind unless bound by society. Largely self-taught, Frankenstein traps himself in his one-man echo-chamber. Much scientific research depends on a clear distinction between observer and observed; sympathy and association depend on seeing other people as yourself. Frankenstein might know a lot about science and galvanism, but he doesn’t know how to be an accountable and productive member of society.

That Frankenstein is based on this opposition between empiricism and friendship gives it an aspect of tragedy, which is amplified by Frankenstein’s (mostly) good intentions causing disaster.

Frankenstein wants to defeat mortality and create a new species that would “bless [him] as its creator and source.” (Freudians might point out that he feels this desire after his mother’s death.)

“Frankenstein might know a lot about science and galvanism, but he doesn’t know how to be an accountable and productive member of society.”

If he wants to create life, why doesn’t he marry his hot fiancée Elizabeth and produce children in a simpler and more pleasurable manner? Domesticity (a feeling of cosiness, one might say) would thwart his selfish desire: “I wished, as it were, to procrastinate all that related to my feelings of affection until the great object, which swallowed up every habit of my nature, should be completed.”

He stays in his “solitary chamber” and doesn’t even write to Elizabeth. Maturity comes from self-denial, and Frankenstein denies himself nothing.

His expectation – “no father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs” – shows that he wants total praise for his creations; he won’t share it with Elizabeth. Victor’s creativity is that of the Romantic genius, owing nothing to society or family or tradition. Revealingly, he regards himself not as a scientist as much as “an artist occupied by his favourite employment.”

After Frankenstein completes his “great object” and animates his creature, a dream reveals the true meaning of his accomplishment. His creation (sometimes called his “daemon”) symbolises the selfish ambition that ruins domestic joy:

“I thought I saw Elizabeth, in the bloom of health, walking in the streets of Ingolstadt. Delighted and surprised, I embraced her; but as I imprinted the first kiss on her lips, they became livid with the hue of death; her features appeared to change, and I thought that I held the corpse of my dead mother in my arms; a shroud enveloped her form, and I saw the grave-worms crawling in the folds of the flannel. I started from my sleep with horror; a cold dew covered my forehead, my teeth chattered, and every limb became convulsed; when, by the dim and yellow light of the moon, as it forced its way through the window shutters, I beheld the wretch—the miserable monster whom I had created.”

The dream becomes real, and the creature kills the people closest to Frankenstein: his younger brother William, Justine Moritz, his best friend Henry Clerval, and finally Elizabeth. (In a fever, Frankenstein begins to recognise himself as “the murderer of William, of Justine, and of Clerval.”)

The creature lacks the initial domestic harmony that Victor enjoyed. The creature tells us in his own words that he was born out of a sort of chaos:

“It is with considerable difficulty that I remember the original era of my being: all the events of that period appear confused and indistinct. A strange multiplicity of sensations seized me, and I saw, felt, heard, and smelt, at the same time; and it was, indeed, a long time before I learned to distinguish between the operations of my various senses.”

Unable to affirm even his birth, he laments his lack of society:

“But where were my friends and relations? No father had watched my infant days, no mother had blessed me with smiles and caresses; or if they had, all my past life was now a blot, a blind vacancy in which I distinguished nothing. From my earliest remembrance I had been as I then was in height and proportion. I had never yet seen a being resembling me or who claimed any intercourse with me. What was I? The question again recurred, to be answered only with groans.”

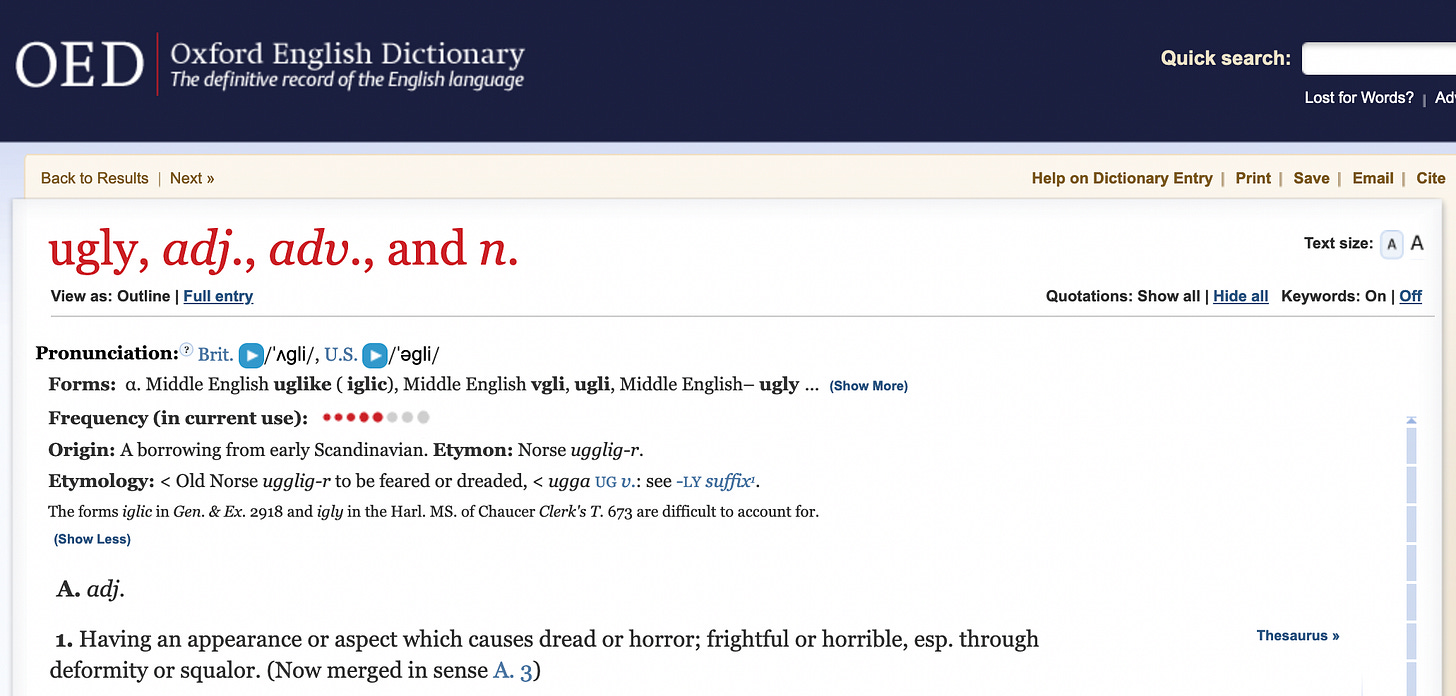

Despite this, he knows that he is ugly, describing himself as “a figure hideously deformed and loathsome … a monster, a blot upon the earth.”

What is it that makes him ugly?

Frankenstein assembled him with parts chosen for their beauty:

“His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips.”

Some philosophers describe ugliness as a lack of beauty, but Denise Gigante argues that the creature is ugly because of his excess. The beautiful features don’t form a harmonious whole. He is bigger and more agile than humans, can bear “the extremes of heat and cold with less injury to [his] frame,” – but this is precisely what makes him horrifying; he tirelessly stalks his creator and threatens him: “I will be with you on your wedding-night.”

He's ugly because he’s offensive and intrusive. (Think of gargantuan office blocks.) If beauty is transparency, a window to the divine, then ugliness is murkiness. (“Hell is murky,” mutters Lady Macbeth.)

Ugliness breaks its bounds, overflows, meddles, and destroys. The ugly creature is Frankenstein’s excessive ambition, which he compares to a natural disaster:

“When I would account to myself for the birth of that passion, which afterwards ruled my destiny, I find it arise, like a mountain river, from ignoble and almost forgotten sources; but, swelling as it proceeded, it became the torrent which, in its course, has swept away all my hopes and joys.”

By presenting the monster’s story in first person and allowing him to describe his actions from his own perspective, Mary Shelley encourages the reader to sympathise with his loneliness and frustration. But his unrepentant violence and lack of accountability prevent him from becoming pitiable.

Frankenstein’s conclusion is that ambition and creative desire must be incorporated into culture and tempered by accountability and self-denial. Shortly before his death, though still unwilling to take responsibility for his creation, Frankenstein partly recognises this. He asks Robert Walton to destroy the creature but adds: “Yet I cannot ask you to renounce your country and friends to fulfil this task.”

The explorer Robert Walton, who recounts the story through his letters, is a failed poet. Early in the novel, he writes to his sister about his “ardent curiosity” and his desire to award an “inestimable benefit… on all mankind.” Like Frankenstein and his creature, Walton is lonely and self-educated.

He never achieves his aim of reaching the North Pole because his sailors ask him to direct the ship back home: “Thus are my hopes blasted by cowardice and indecision; I come back ignorant and disappointed.” But he’s not completely ignorant: unlike Frankenstein and the creature, Walton learns that he’s accountable to others, and that some things (the safety of his sailors) are more important than his desires. He learns his limits. He survives.

ENTER THE OGRE

Like Frankenstein’s creature, Shrek destroys the beautiful. The first scene of the movie shows him tearing a page from a charmingly illustrated book and using it to wipe his arse. He lives alone on a swamp. He washes with mud and fishes with farts. People find him repulsive, which understandably makes him bitter, but Shrek is socialised first through his friendship with Donkey (who tells him he’s “got to try a little tenderness” because “chicks love that romantic crap”) and then through his relationship with Fiona.

The destructive character is Lord Farquaad, the megalomaniac ruler of Duloc. Like Frankenstein, Farquaad is obsessed with himself. Both seek to control what they can’t: Frankenstein by eliminating death, Farquaad by ridding his perfectly uniform kingdom of Fairy Tale creatures. He wants to marry Fiona to improve his social position, not to share his life with someone else. As Shrek disrupts his wedding to Fiona, the Lord of Duloc shouts, “I will have order, I will have perfection!” before being eaten by the dragon.

Frankenstein and Farquaad share the sin of pride: the sin of Satan, Prometheus, and the Tower of Babel. Shrek may be the hideous ogre, but he’s free of the moral deformities afflicting Frankenstein and Farquaad. He’s peaceably incorporated into society through marriage, the option unavailable to Frankenstein’s creature.

Problems arise from self-centredness because relationships give life meaning. You realise that your “self” is layered with parts that are not you.

Ogres have layers. Daemons do not.

One of the differences between Shrek and Frankenstein's creation is that Shrek has been happy and content in his world for many years. He has no desire or apparent need for more. The Donkey (not unlike the serpent in Eden) makes him aware of a different, greater world possible. It is only then that Shrek finds his world inadequate.