Knowing that I studied Classics, my students kept asking me if I’d read Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, a retelling of the ancient love story between Achilles and Patroclus.

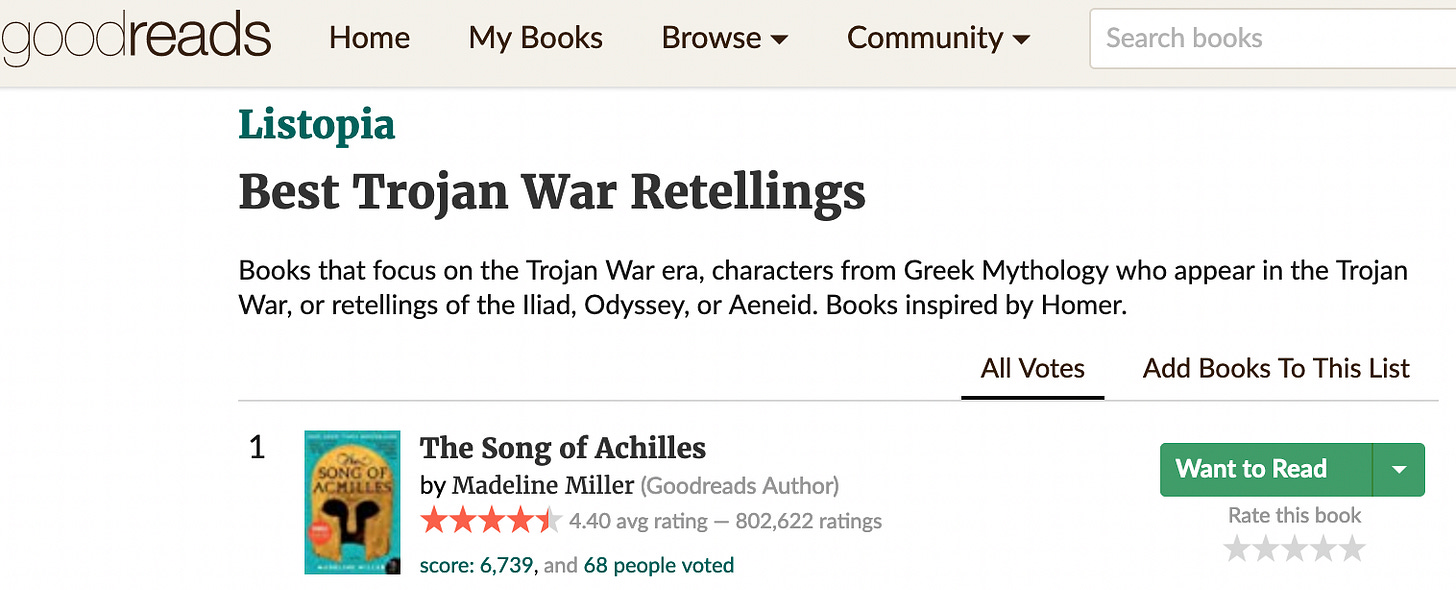

The novel is hugely popular, has a massive rating on Goodreads, won the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2012, and received a boost in sales after a video on TikTok went viral in 2021. Most professional book reviewers praised the novel. In The Guardian, Natalie Hynes wrote that “Miller’s prose is more poetic than almost any translation of Homer,” which is perhaps a rare example of exaggeration in a newspaper famous for its equanimity and dispassionate analysis.

I’ve heard a few people grumble that Homer never mentions that Achilles and Patroclus were lovers. That’s true. The idea isn’t Homeric, but it is classical: both Aeschylus and Plato describe Achilles and Patroclus as a romantic couple. (Though the novelist isn’t obliged to cite sources when retelling stories from the classical world.)

I can see why The Song of Achilles is so well-liked: Miller describes some things very well, her comparisons are unusual yet apt, and some of her characters are vivid and interesting. (As we shall see, I’m not the only one who liked her depictions.)

The main reason for the novel’s popularity, I assume, is that, despite the ancient Greek covering, at heart The Song of Achilles is a young adult romance novel with plenty of sensuality.

Patroclus, the narrator, is a twink with no apparent skills or personality.

Why does Achilles fall in love with him? Don’t know.

The emphasis on their infatuation wouldn’t be so much of a problem if Miller didn’t keep trying to convince the reader that her novel is set in the ancient world; The Song of Achilles lacks the understanding of the past and its ideals that can make historical fiction credible and immersive.

Retelling parts of the Iliad in an American idiom and mindset, the novel awkwardly includes throwaway lines to try and capture an ancient Greek way of life:

“Briseis was a war prize, a living embodiment of Achilles’ honor. In taking her, Agamemnon denied Achilles the full measure of his worth.”

“[Briseis] is in Agamemnon’s custody, but she is Achilles’ prize still. To violate her is a violation of Achilles himself, the gravest insult to his honor.”

“They have dishonored [Achilles]. They have ruined his immortal reputation.”

“Our world was one of blood, and the honor it won; only cowards did not fight.”

“It was not so much about the worth of any object as about honor.”

It's bad enough to blandly assert these things, but most of the time Miller’s characters don’t seem to believe them. For two-thirds of the novel, Achilles doesn’t care what people think or say about him. After Agamemnon takes Briseis from him, he complains about the insult to his honour.

Why does he care about it now? Don’t know.

Achilles is the greatest warrior of his generation, but he and Patroclus spend most of the novel admiring each other’s beauty, avoiding war, playing the lyre, and making the beast with two backs. They don’t resemble their Homeric counterparts. They resemble the Homeric Paris.

In the Iliad, Hector scolds Paris, who is avoiding the duel with Menelaus, for his good looks, music, seduction of women:

“Evil Paris, beautiful, woman-crazy, cajoling,

better you had never been born, or killed unwedded…

And now you would not stand up against warlike Menelaos?

Thus you would learn of the man whose blossoming wife you have taken.

The lyre would not help you then, nor the favors of Aphrodite,

nor your locks, when you rolled in the dust, nor all your beauty.”

(Iliad 3.39-55. All Iliad translations are from Lattimore’s version).

Later in the Iliad, Paris is spirited away from the battlefield. While Menelaus is looking for him, he’s waiting for Helen in his bedroom, “shining in his raiment and his own beauty.” (3.392-4).

There are many splendid ironies here. The first is that, while Andromache loves her warrior-husband Hector, Helen despises Paris. In the Iliad she begs Aphrodite:

“Will you carry me further yet somewhere among cities

fairly settled? In Phrygia or in lovely Maionia…

but stay with [Paris] forever, and suffer him, and look after him

until he makes you his wedded wife, or makes you his slave girl.

Not I. I am not going to him. It would be too shameful.

I will not serve his bed, since the Trojan women hereafter

would laugh at me, all, and my heart even now is confused with sorrows.” (3.400-420).

When Helen sees Paris, she derides him: “So you came back from fighting. Oh, how I wish you had died there / beaten down by the stronger man, who was once my husband.” (3.428-429).

The other irony is one that Miller doesn’t seem to be aware of. Choosing a life of pleasure (Aphrodite), Paris dooms Troy to the destructive wrath of Athena and Hera:

“For we two, Pallas Athene and I [Hera], have taken

numerous oaths and sworn them in the sight of all the immortals

never to drive the day of evil away from the Trojans,

not even when all the city of Troy is burned in the ravening

fire…” (20.313-316).

Choosing a life of pleasure (Aphrodite), Miller’s Achilles and Patroclus are rewarded with glory and a best-selling novel. How modern! How American! How sentimental! Miller’s Achilles and Patroclus would rather be loving than fighting and are more interested in their own amorous feelings than in anything else. They grow tall but they don’t grow up.

Why did this novel need to be set in the ancient world? Don’t know.

I can understand some of the thinking behind it: no longer interested in military heroism (or hostile to it), the modern novelist retells old stories from different perspectives, especially ones unsung by Homer. Ancient stories must be made to espouse modern values.

There’s nothing wrong retelling Homeric stories, though Euripides did it first, and seemed to have a special interest in the women of myth. A partial list of his plays includes Andromache, Hecuba, Electra, The Trojan Women, Iphigenia in Tauris, Helen, and Phoenician Women. Queen Elizabeth I translated Euripides into Latin, and Lady Jane Lumley was the first to put his Iphigenia in Aulis into English.

Why is it considered a revelation when an ancient story is told from a female perspective? Don’t know.

Pat Barker has a woman as the narrator of her 2018 novel The Silence of the Girls, another retelling of the Iliad, this time (mainly) from the perspective of Briseis. She starts the novel with a complaint:

“Great Achilles, brilliant Achilles, shining Achilles, godlike Achilles… How the epithets pile up. We never called him any of those things; we called him ‘the butcher.’”

Achilles is a butcher? Where have I read that idea before?

The Song of Achilles: “Achilles flourished. He went to battle giddily, grinning as he fought. It was not the killing that pleased him – he learned quickly that no single man was a match for him. Nor any two men, nor free. He took no joy in such easy butchery, and less than half as many fell to him as might have.”

The Song of Achilles again: “‘She is mine,’ Achilles said. Each word fell sharp, like a butcher cutting meat.”

I’m not suggesting that Pat Barker has plagiarised Madeline Miller’s work – only that the two novelists share a way of retelling the Iliad which doesn’t resemble any ancient Greek worldview.

Is the point of historical fiction to transcend ourselves and our current circumstances, or to show how the past fails to meet modern standards? Don’t know.

Reading these adaptations, I get the feeling that the modern novelist isn’t responding to Homer but to contemporary interpretations of Homer. Despite the many retellings of the Iliad, one perspective remains unexplored: that of Achilles’ horses. During the Trojan War, they talk to him and mourn his death – enough material for a writer to start riffing on.

Is there a novelist brave enough to retell the story from the horses’ perspective? Don’t know.

This book is probably the reason why people look at me strange when I say Patroclus is one of my favourite characters in Homer. It's a shame that a figure so unique and endowed with values such as loyalty, courage, and considerable martial prowess has become a twink without personality in the popular imagination.