Over at Pens and Poison, the talented Liza Libes recently published “Why We Should Free Literary Study from Marxist Proponents,” arguing that “ideological extremism” is endangering the humanities. Although I have some sympathy with Miss Libes’s argument – most English departments teach a load of crap – I think she has made some hasty generalisations.

She describes her experience at a prestigious American university:

From the moment I stepped foot on campus to study English Literature at Columbia University, I felt that something was amiss. My freshman year of college, for instance, the university had removed Ovid’s Metamorphoses from an introductory freshman literature course called “Masterpieces of Western Literature” because several students had complained about its “graphic”—the work is far from graphic—depictions of rape.

Removing the Metamorphoses was an appalling decision – and further confirms my view that the American Revolution was a mistake – but I’m not sure it’s representative. At the University of Sydney, I spent two years reading Ovid (in Latin) and the only things preventing me from studying more were the cheap drinks at Manning Bar.

Miss Libes continues:

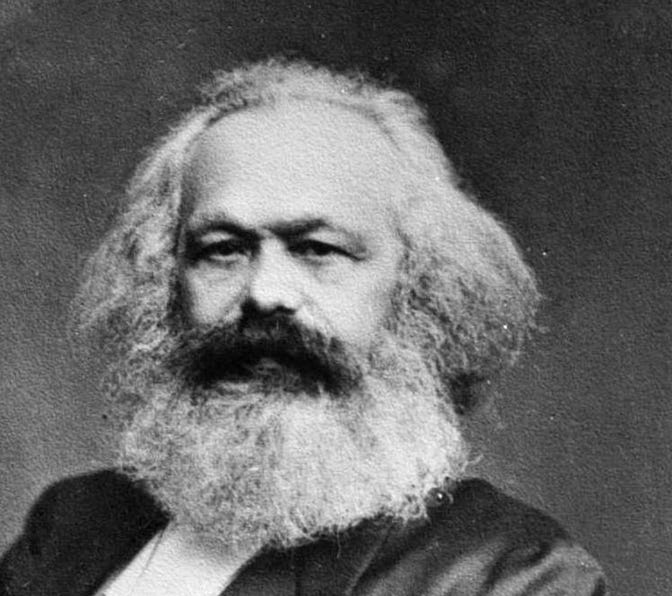

Over the next four years, I grew increasingly disheartened by the volume of literary theory assigned throughout my English classes. I had arrived at Columbia intending to become a humanistic scholar, which is what was advertised to me during my application process. Yet, I found the vast majority of critical theory readings not only biased but also far off the mark: I was asked to understand Jane Austen’s early 19th-century novel Mansfield Park under the 20th-century postcolonial lens of the notorious anti-Semite Edward Said, and I was fed Karl Marx in nine out of the sixteen literature courses that I took during my time as an undergraduate student… Where Marxists did not find a voice politically, they found it in the study of literature—a field so subjective that no one could call out these extremist takes as erroneous… Across American college campuses, English literature students are being taught that literary study must necessarily rest on the far-left ideologies of Karl Marx, Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, and others.

Besides contentious judgements of Edward Said, the williambuckleyesque thrust of the argument is misleading; blaming everything on Marx is positively scandalous.

Considering Marx had a substantial knowledge of Latin and Greek and opposed press censorship, I doubt he would have approved Columbia’s decision to remove Metamorphoses from the syllabus. I spent six years at university, and during that time met only one Marxist: a vivacious, straight-talking expert on Greek history who would have sooner told the bureaucrats to suck eggs than remove an important text from his course. What the Columbia decision really exposes is the strain within American liberalism: the tension between liberals defending the right to freedom of speech (including racist, sexist, and otherwise hurtful language) and liberals defending the right to live unharmed. No matter what your views are on this tension, it has very little to do with Marx.

Neither do the concepts that Miss Libes censures. She dislikes critical theory because of its biases (fair enough) but many critical theorists, though they sometimes called themselves Marxists, developed their ideas by answering, correcting, and scolding classical Marxism. Jean-François Lyotard, one of the poster boys of critical theory, rejected Marxism and supported Valéry Giscard d’Estaing over the Socialist Party’s François Mitterrand in the 1974 French election. When Miss Libes groups “Karl Marx, Michel Foucault, Judith Butler” under the banner “far-left,” she obscures that these writers have different emphases, different styles, different goals.

Despite her anger and polemical flair, Miss Libes doesn’t provide a counter-argument to Marxist readings of literature. I am not a Marxist, but if being one means being attentive to a literary work’s social and historical context, what is objectionable about that? A Marxist might not only look at the income disparities in Jane Austen but also ask: what cultural and material factors made the production of novels possible? You might not be interested in these questions, but to say that asking them “endangers” the humanities is preposterous.

In fact, I think that our dying literature departments need more Marxists. Karl Marx loved Shakespeare. He had “Shakespearomania”. He read Shakespeare, quoted Shakespeare, recited Shakespeare. When arrived in England, he learned English partly by memorising Shakespeare.

He passed on his love to his daughter Eleanor, who co-founded a Shakespeare reading club (the Dogberry Club) and wrote that Shakespeare was “the bible of our house, seldom out of our hands or mouths.”

Every English professor must follow the example of Karl Marx: venerate Shakespeare, and pass on this love to your children!

Appreciate this response! I am not sure it quite takes into account the perils of Marxist ideology, however. I am more than certain that Marx himself would have been appalled at the people who call themselves Marxists in the academy today, and that seems to be the primary critique here. That does not discount, however, the danger that his ideologies have posed historically. One must only look to the Soviet Union or Mao's China for a real assessment of what Marxist ideology devolves into when brought into the academy.

You can pose whatever sorts of questions you will about the world—but some questions have dangerous consequences. And, as I said in my article, applying a Marxist critique to literature is missing the point of what literature is supposed to be.

Also yes—I am using "Marxist" as a stand-in for far-leftist, which one can argue *is* reductive, but that is simply because the far left is so homogenous in their thinking that I almost guarantee you that every single one of them will self-identify as a Marxist.

Thanks again for writing! Enjoyed reading this piece, though we may have some disagreements :)

Well you two seem to be sorting this out, but "Marx" and variants has become a complex of meanings and usages that are difficult to untangle in real time and across oceans. The obvious analogy would be "liberal." When I was a kid, and at some point with the SPD in Germany, there were actual Marxists. Really. And I was not, but read a fair amount of Marx, etc. And then the world changed, and lots of folks have detected a Marxian sensibility, maybe, in some of my own attention to economic situation, especially in my critique of folks that Liza might call "Marxists" but wouldn't for reasons you suggest . . . Anyway, I'm not going to attempt a real intellectual history, but I think that's what's required if one really wants to straighten things out. Sounds like work. For now, you are both doing great work, and I appreciate the civilized exchange!