Can you ever have too many movies about the Second World War? Yes and no. Yes, because the education system is so bad in the Anglosphere that movies have become the main source of historical knowledge. As a result, too often the war against Nazism is a facile reference point for lazy journalists. Trying to vitalise the discussions about current affairs, and attempting to give a historical perspective, they mindlessly appeal to the Second World War for parallels, but by doing so they tend to sound hysterical, and the inaccuracy of their comparisons makes their reporting less clear. If every evil man is Hitler, if every act of hostility is the invasion of Poland, if everyone you don’t like is a Nazi, what words remain to describe the enormity of the Second World War and the horrors of the twentieth century?

On the other hand, hardly any other period in history provides so much material for the study of egomania, persuasion, propaganda, hypocrisy, sacrifice, heroism, deception, barbarism, compassion, and the moral dilemmas where every option leads to tens of thousands of deaths.

Recently, the decrease in the quality of films has coincided with the increase of pre-release publicity campaigns. Hype has replaced craft. What we’re left with are multi-million dollar blockbusters worth almost nothing. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the movies dealing with the Second World War, a genre that is now famous for films that are visual triumphs and moral failures: Schindler’s List comes to mind, so does Saving Private Ryan. But the worst example is Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, which is supposedly about the power of art to overcome evil but is really the triumphalist fantasy of a juvenile fanboy. In my view, these films are nowhere near as good as The Pianist, leaving us in the strange situation where the only big director to make a morally serious film about the Second World War is Roman Polanski.

Where does Christopher Nolan’s recent release Oppenheimer fit in? Other than Barbie, it’s hard to think of a film this year that’s had more hype, but some of it is deserved. Mr Nolan’s technical mastery is indisputable, and the cast gives some brilliant performances. Yet the film is about an hour too long and is emotionally sterile: even the sex scenes aren’t sexy.

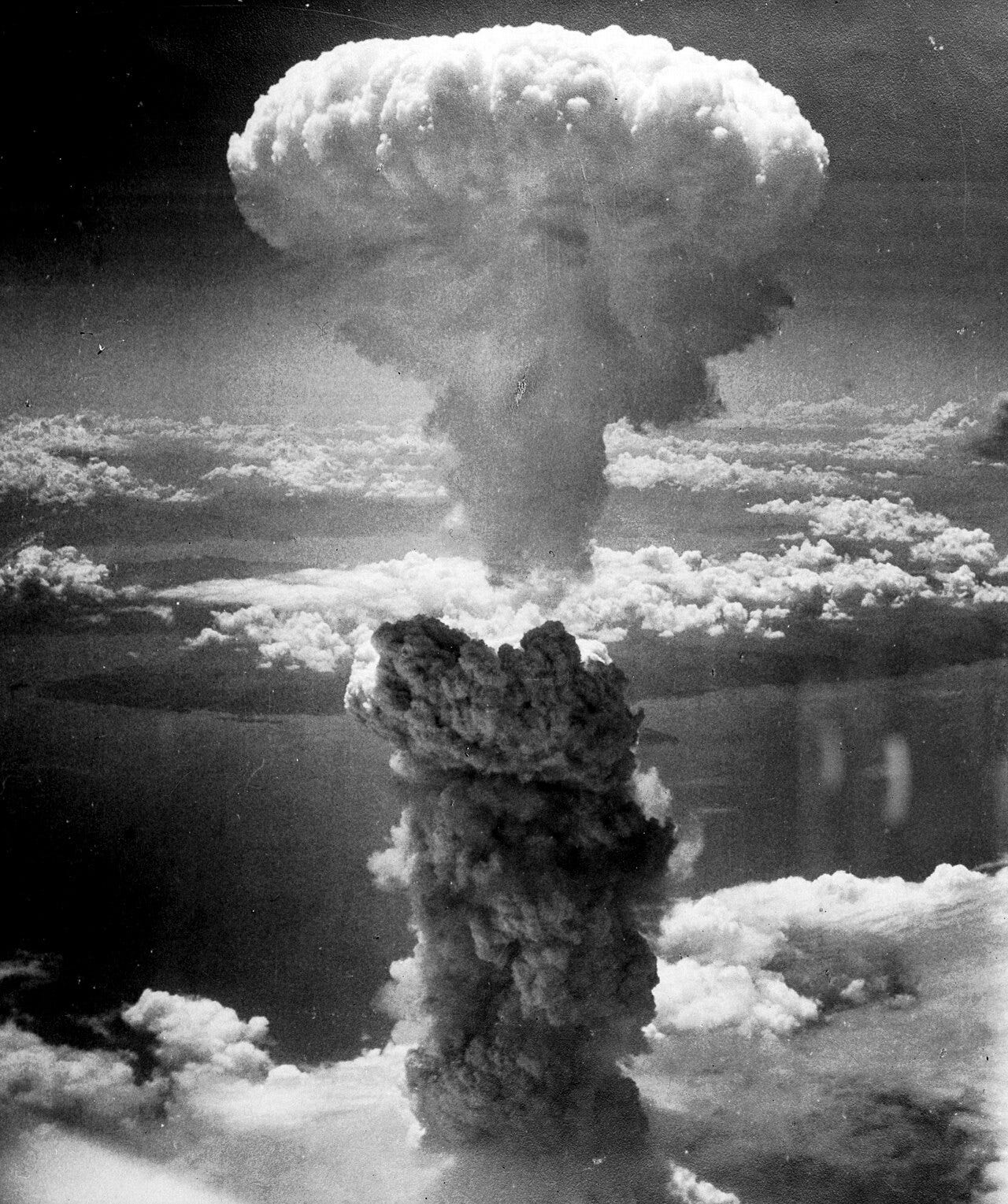

Oppenheimer contains two potentially good movies: one about the Manhattan Project, and another about J. Robert Oppenheimer’s post-war reputation and his supposed connections with Communism (though Mr Nolan seems to lack basic knowledge in this area, such as the difference between Marx and Proudhon). Each would have made an excellent movie on its own, but, strangely, one of the most interesting and important questions is glossed over in both: the moral question about dropping the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Apart from some brief moments – a man vomiting near a bike rack after hearing about the first bombing, Mr Oppenheimer himself sharing his doubts with President Truman – the emotional and moral import of the atomic bombs isn’t emphasised.

And it should be. How can anyone make a film 180 minutes long and spend so little time on the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians? You might answer that the film is about Mr Oppenheimer, the famous physicist – but what is he famous for, if not the atomic bomb? And what is the bomb famous for, if not those deaths?

I am aware of the arguments claiming that the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was justified. Here is Clive James in his magnificent book Cultural Amnesia:

“…once the reader is launched on the study of a war so huge and horrible, he should be prepared at least to consider the unpalatable proposition that the quick ending of it by recourse to the atomic bombs was not only inevitable, but justified.”

What could justify them? I don’t know what Sir Antony Beevor’s opinion on the subject is, but he presents the facts very clearly in his one-volume The Second World War:

“On the basis that approximately a quarter of Okinawa’s civilians had died in the fighting there, a similar scale of civilian casualties on the home islands would have exceeded many times over the numbers killed by the atomic bombs.”

The main point of this argument is that an invasion of Japan would have been far bloodier than the bombings. I used to find this argument convincing. It’s probably true, at least from a military standpoint. But is it a good moral argument?

I began to reconsider the question after reading the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe. In 1958 she wrote a pamphlet called “Mr. Truman’s Degree,” protesting the decision by the University of Oxford to award Harry Truman an honorary doctorate. She thought Truman was a murderer. She was aware of the aforementioned argument in support of the bombings, but maintained that we can calculate the good and bad consequences of an act only if the act itself is not intrinsically evil. To think otherwise is to subscribe to what philosophers call consequentialism. Supporters of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki use consequentialist arguments. In response, Elizabeth Anscombe argued that intentionally killing civilians is evil, therefore absolutely impermissible, whatever the consequences. She wrote: for “men to choose to kill the innocent as a means to their ends is always murder, and murder is one of the worst of human actions.”

There are some who contend that the war in the Pacific was a “total war,” and take “total war” to mean that the economic and social strength of a nation contributes to its military strength. Therefore, there’s no distinction between civilian and combatant. Elizabeth Anscombe had a withering response: “I am not sure how children and the aged fitted into this story: probably they cheered the soldiers and the munitions workers up.”

She made a further point: the reason an invasion of Japan would have been so bloody is because of the Allied insistence on unconditional surrender. Obviously, an enemy is going to fight with everything they’ve got if you make such demands. Thus, the atomic bomb was the “solution” to a problem that the Allies themselves had created.

Here, too, Mr Nolan’s Oppenheimer omits some important details. A few times in the film, Matt Damon’s character refers to the Potsdam Conference, which was held in July-August 1945. The film makes no mention of the fact that, at that conference, Stalin told the Allies he’d received requests from the Japanese to act as a mediator with a view to ending the war – requests he’d refused.

But the details get a bit messy (Henry Stimson’s War Department had intercepted and decoded the messages between Japan and the Soviet Union, and Stalin was planning to invade Manchuria) so let’s focus on the idea of consequentialism.

Elizabeth Anscombe developed her criticism of it in a later pamphlet, “War and Murder.” She distinguished choosing to kill the innocent as a means to an end – which is always murder – from choosing to do something else which will probably or certainly kill the innocent. Bombing civilians to destroy morale and encourage surrender is clearly an example of the first case; the second case might also be murder, depending on the details. Strikingly, Elizabeth Anscombe blamed pacifism (the belief, quite popular among intellectuals in the 1920s and ‘30s, that fighting in wars is always wrong) for moral depravity: “pacifism teaches people to make no distinction between the shedding of innocent blood and the shedding of any human blood.” While pacifism is wrong, so too is the idea that a state may do anything to defend itself. Deliberately killing the innocent is murder, and murder is always unjust.

The consequentialist must accept some ugly things. The common example is that of a judge who condemns an innocent man to satisfy a violent mob that would otherwise kill hundreds of people. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it’s roughly the plot of To Kill a Mockingbird, which presents Atticus Finch as a hero because he defends justice despite the consequences. According to the consequentialist, however, the “good” of the placated mob outweighs that of justice.

Here’s another example, one borrowed from Bernard Williams:

Andy has just completed a doctorate in chemistry but struggles to find a job. His health isn’t very good, which limits the number of jobs he might be able to do well. His wife has just found some part-time work, but this causes a great deal of stress, since they have small children and have severe problems looking after them. The results of all this are incredibly damaging, especially on the children. An older chemist knows about this situation and says that he can get Andy a decently paid job in a lab which conducts research into chemical weapons. Andy says he refuses to do such a job because he’s opposed to chemical warfare. The older chemist replies that he’s not too keen on it either, but if Andy doesn’t accept the job someone else will, and there happens to be an applicant who is particularly enthusiastic about the research. In fact, the older chemist is offering the job not only out of concern for Andy and his family but out of alarm about this other man’s fervour. Andy’s wife thinks that there’s nothing particularly wrong about research into chemical weapons. What should he do?

In this situation, it seems the consequentialist would say that Andy should accept the job; the consequentialist might even say that it’s obvious Andy should accept the job. But I suspect many people would wonder about it. Bernard Williams argues that the problem with consequentialism is that it cuts out an important consideration: that each man is responsible for what he does, rather than for what other people do. Consequentialism alienates people from their moral feelings. No one can be expected to abandon his life and projects to adopt the “impartial” worldview of the consequentialist. In other words, consequentialism leaves no room for the notion of integrity. (Here, Williams is using “integrity” in its literal sense, meaning the condition of having nothing taken away, of being undivided or unbroken.)

Some consequentialists would respond to these objections by providing a modified system called “rule consequentialism,” which argues that an action is morally right if it doesn’t break a rule whose public acceptance would have the best consequences. But even this can lead to some embarrassing conclusions.

Suppose there’s a well-ordered, stable society offering the best possible situation to most citizens, but there’s a small racial minority which does no harm while not contributing much benefit, either. The majority have such a strong prejudice that they find the sight of this racial minority – even the thought of them – unpleasant. With a view to alleviating their unpleasant feelings, the majority make proposals to remove the minority, or even torture them. What if the rules of this society then require the punishment of the innocent racial minority? How would the consequentialist oppose this? He could say that the injustice of such a system is so great that no number of good consequences could ever justify it, but then he’s working with a non-consequentialist idea of right and wrong.

I have only highlighted a couple of the problems with consequentialism, and there’s much more to say about the topic. It’s easy to justify murdering the innocent when you use vague abstractions such as “the Japanese” or “the Germans” as opposed to specific military and government personnel. With Oppenheimer, Mr Nolan had a great opportunity to remind us of the unimaginable evil that has been done in the name of “good intentions” and “defeating the enemy.” He blew it. At its best, what film can do is portray the varied and individual lives hidden under the abstractions and stereotypes.

If those who support the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could see what those acts really were – the intentional killing of innocent people in order to shock the survivors into surrendering – then perhaps they wouldn’t approve them with such high zest.

But, with Mr Nolan’s Oppenheimer, the hundreds of thousands of civilians destroyed by the atomic bomb remain a footnote to the biography of a brilliant physicist.

it is wrong to force a minority (or an individual) to make a sacrifice in favour of a majority. there's always a choice: people are far too smart to agree to a binary choice of "if we don't do it, the others will" (or some such). also reminds me of the trolley problem - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem

Astonishing that the movie doesn't "problematize" this, which used to be a staple of leftist thought (and justifiably so). Consequentialism as an ideology/worldview is a poison in my view and the bomb shows it: even accepting the (dubious) claim that it was justified unter utilitarian reasoning, those who justified it showed their true moral colors by conveniently sneaking in other ends: the testing of the bomb under real-life conditions, and the total surrender by Japan for geopolitical reasons that had nothing to do with ending the war.