Last week, the great music educator Rick Beato published a video asking why “people are addicted to speed.” He wasn’t talking about drugs, but the adrenaline we get from watching elite athletes or listening to crack musicians, the “visceral” reaction when we encounter people expanding the limits of human ability. His video opens with a reference to the Olympics, suggesting that athleticism and competition are as important in music as they are in sports.

I disagree. Mr Beato says that playing musically is more important than playing quickly, but then goes on to say “I never hear people who have spent the time to develop their chops – which takes years – say ‘I like people who play melodically.’”

Well, I have spent a bit of time (19 years) developing my chops, and I like people who play melodically.

Don’t mistake me, reader – I like high-octane playing more than your average person. When I was a teenager, I spent hours every day developing my chops in an effort to imitate my heroes who play guitar with white heat. At first, I thought my advanced technique distinguished me from other players, but I soon learned that nothing is easier to imitate than technical dexterity. Speed can be counterfeit.

Speed is often a crutch for people who can’t do anything else. Despite Mr Beato’s analogy to sports, in music it’s usually harder to play at slower tempos. Beginners often feel nervous or pressured and try to fill the gaps with an endless flow of sounds – musical diarrhoea. They play so many notes because they’re looking for the right one, said B.B. King, who always managed to find the right note despite playing comparatively few of them.

Sure, players with great chops often bring exuberance and excitement, but if they’re going to be anything more than bombastic showmen, they’re going to bring something else, too. The daredevil may change your evening but he’s not going to change your life.

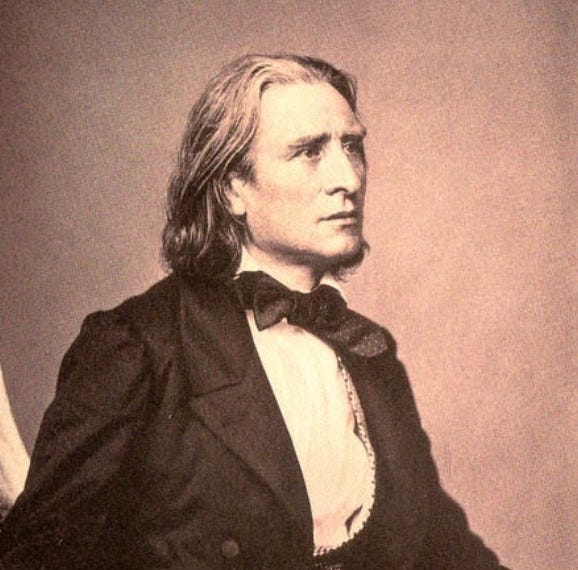

Franz Liszt might be the archetype: the circus performer of the recital hall, who ostentatiously went through three pianos in an evening the way a rockstar smashes his guitars. (The pianos of the 1830s and 40s were feebler than their modern counterparts.) “List: or the school of running – after women,” said Nietzsche, possibly envious that women weren’t running after him. But Liszt could hold back when he needed to. His variations on Bach’s Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen are quite touching:

His lesser-known piece “sunt lacrimae rerum” (“there are tears of things”) takes its title from Virgil’s Aeneid, where the words refer to the fall of Troy. Liszt’s title alludes to the failed Hungarian revolution of 1848-9. But the piece is dedicated to Liszt’s student Hans von Bülow, whose life was ruined because his marriage to Liszt’s daughter was wrecked (according to Liszt) by Wagner. There are tears in this work. Listen to the sadness of the bass notes:

You can find similar examples in every genre. Charlie Parker is famous for playing over rapid chord changes at impossibly fast tempos, but in my view, he rarely played better than he did on the slower number “My Old Flame”.

Mr Beato is a guitarist, so he should know better than anyone how players with great chops can do nothing for an audience except cause lesions in the ears and aches in the guts. The “shred guitar” movement started with great players such as Eddie Van Halen and Joe Satriani, but ultimately spawned a legion of players memorable for their revolting incoherence. What they lack in phrasing, they make up for in pace. The only thing moving faster is the audience fleeing.

Even among this group, though, there are players with a gift for rhythm and melody. Paul Gilbert was the guitarist for the cheesy band Mr. Big and has since developed a very successful solo career. Here he is covering a schmaltzy Spice Girls song, but the first guitar solo is incredibly expressive:

The progressive metal band Dream Theater are known for a demanding style of music played with surgical accuracy; the guitarist John Petrucci released an instructional video called Rock Discipline, suggesting that his style is robotic and soulless. Few guitarists can play faster than him, but few guitarists have his gift for melodic phrasing. He still has a huge fanbase; all his clones are forgotten. Listen to the poignant and moving part of “About to Crash” starting at 4:21. Every note is perfectly chosen as the guitar soars above the sparse accompaniment.

A virtuoso knows that technique is a means, not an end in itself. Given enough time, anyone can develop musical agility. To rouse the soul of an audience, to stir their emotions, to inflame their yearning for connection and meaning? That’s much harder. That’s the greater accomplishment.

What are your favourite slower pieces of music? Leave a comment and let me know!

A good example of fast v slow might be Glenn Gould’s two recordings of the Goldberg Variations. Almost 30 years apart. Gould said his technical abilities were pretty much the same. The Aria in the second recording is half the speed of the first! ‘55 recording: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5nCQV_mywLk ; ‘81 recording: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=43sTxRVpRBM. But three of my favourite slow pieces would be Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, Vivier’s Lonely Child, and the 8th movement of Messaen’s Quartet for the End of Time :).

I’m a JJ Cale devotee. And yes, it’s very hard to play so laid back you’re almost falling off the stage.