“Tush,” is the first word of Othello. Roderigo is speaking to Iago, who replies with an oath, “’Sblood,” a contraction of “by God’s blood.”

The first word of Hamlet, “who’s,” introduces a play about identity (and other things), while the first word of Macbeth, “when,” introduces a play about time and the fulfillment of prophecies (and other things).

Shakespeare had plenty of experience writing about soldiers, but Othello is the first of his plays with foul-mouthed officers, preceding Gunnery Sergeant Hartman in Full Metal Jacket by about 384 years. The play is full of profanities: “’Zounds,” “pish,” “a fig!” They don’t sound like much, but remove them (they’re not in the First Folio) and, as Frank Kermode argues in his great book Shakespeare’s Language, the tone of the play is considerably different. The coarse language is appropriate to the military setting of the play, but is more significant in expressing one of the major themes: sexual jealousy and disgust.

At the start of the play, we learn that Othello, a General of the Venetian army, has recently promoted Michael Cassio instead of Iago. Salty about this, Iago desires revenge.

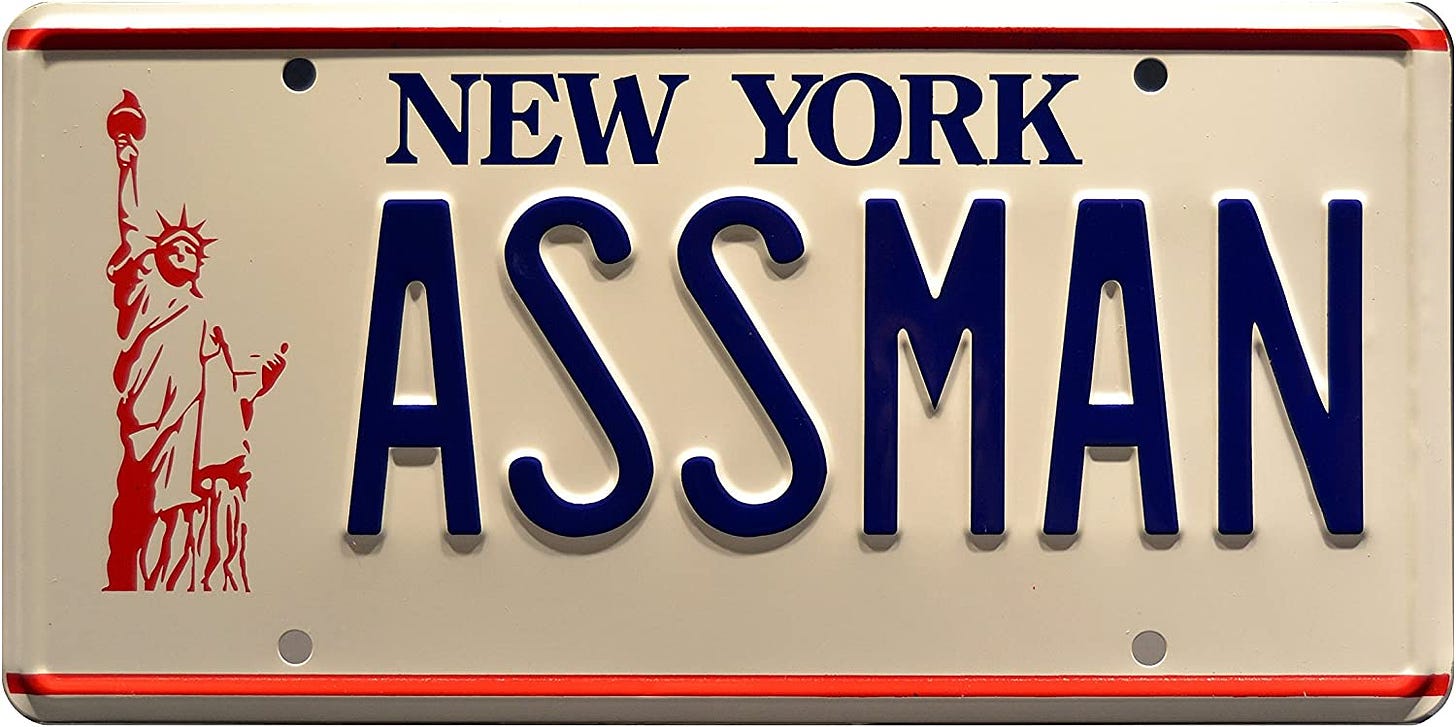

The loyal, dutiful man “wears out his time, much like his master’s ass, / for naught but provender.” Not wanting to be an ass, Iago will continue to serve Othello, but only to further his own ends. When the time is right, Iago will get payback.

He’ll get it using his genius for obscenity. After Othello elopes with Desdemona, Iago and his accomplice Roderigo cause a fuss in the streets. They wake up Desdemona’s father, Brabantio. Iago tells him that his daughter has eloped and is now enjoying marital pleasure with her new husband, “the Moor.” Except that’s not how he puts it.

Not only has the pure, noble, Venetian Desdemona married in secret, she has married a black man: “Even now, now, very now, and old black ram / Is tupping your white ewe.” Iago continues the motif of animal copulation: Desdemona is being “covered with a Barbary horse” – Brabantio’s descendants will “neigh” to him.

Iago’s descriptions – full of sexual and racial loathing – contrast with what we see of Othello and Desdemona. They’re deeply in love, despite their differences. Desdemona was actually the one who pursued Othello; what made him attractive was how he told the stories of his military career. Iago’s language is course and vulgar; Othello’s is grandiloquent. As befits a General in the Venetian army, he speaks with fluent self-confidence. He can sway the senators at a meeting and can command an army on the battlefield. Only Iago’s toxic coarseness can break Othello’s nerve. Iago will make Othello believe that Desdemona is having an affair with Michael Cassio. Othello will “as tenderly be led by the nose / as asses are.”

Iago has no scruples about this. Marriage means nothing to him: love “is merely a lust of the blood and a permission of the will.” The bawdy scene with Desdemona at the start of Act II (almost always cut from productions) shows that Iago has no use for the language (or the idea) of courtship. He hates women. He gloats about how Othello will reward him for exposing the “proof” of Desdemona’s infidelity: Othello will thank Iago “for making him [Othello] egregiously an ass, / and practicing upon his peace and quiet / even to madness.”

Othello’s madness is clear from Act III, Scene iii, one of spiciest scenes in Shakespeare. Desdemona contributes to her own doom by praising the honesty of Iago. When she leaves, Othello speaks of his love for her: “and when I love thee not,” he says in a couple of lines full of foreboding, “chaos is come again.” Now, Iago gets to work and starts raising suspicions about Cassio:

IAGO: My noble lord –

OTHELLO: What dost thou say, Iago?

IAGO: Did Michael Cassio, when you woo'd my lady,

Know of your love?

OTHELLO: He did, from first to last. Why dost thou ask?

IAGO: But for a satisfaction of my thought;

No further harm.

OTHELLO: Why of thy thought, Iago?

IAGO: I did not think he had been acquainted with her.

OTHELLO: O, yes; and went between us very oft.

IAGO: Indeed!

OTHELLO: Indeed! Ay, indeed: discern'st thou aught in that?

Is he not honest?

IAGO: Honest, my lord!

OTHELLO: Honest! Ay, honest.

IAGO: My lord, for aught I know.

OTHELLO: What dost thou think?

IAGO: Think, my lord!

OTHELLO: Think, my lord!

By heaven, he echoes me,

As if there were some monster in his thought

Too hideous to be shown.

Previously graceful and articulate, Othello’s speech has been reduced to slight, simple words. He demands that Iago give him proof of Desdemona’s affair with Cassio. Iago asks: “Would you, the supervisor, grossly gape on? / Behold her topp’d?” Re-introducing the images of animal lust, he asks if Othello wants to see Desdemona and Cassio in the act, while they were “as prime as goats, as hot as monkeys.”

Soon, the enchanted handkerchief that Othello gave to Desdemona as a token of their love becomes the subject of conversation. “A sibyl” gave the hanky to Othello’s mother. It had the power of controlling his father’s love for her; if she lost it, his father’s eye “should hold her loathed.” Desdemona lost it. Othello demands to know where it is, and it’s hard to imagine a scene so dramatically intense, as she lies about it and begs Othello to re-instate Cassio, who just got fired for drinking on the job:

OTHELLO: Is't lost? Is't gone? Speak, is it out o' the way?

DESDEMONA: Heaven bless us!

OTHELLO: Say you?

DESDEMONA: It is not lost; but what an if it were?

OTHELLO: How!

DESDEMONA: I say, it is not lost.

OTHELLO: Fetch't, let me see't.

DESDEMONA: Why, so I can, sir, but I will not now.

This is a trick to put me from my suit:

Pray you, let Cassio be received again.

OTHELLO: Fetch me the handkerchief: my mind misgives.

DESDEMONA: Come, come;

You'll never meet a more sufficient man.

OTHELLO: The handkerchief!

DESDEMONA: I pray, talk me of Cassio.

OTHELLO: The handkerchief!

DESDEMONA: A man that all his time

Hath founded his good fortunes on your love,

Shared dangers with you —

OTHELLO: The handkerchief!

DESDEMONA: In sooth, you are to blame.

OTHELLO: ‘Zounds!

It’s essential to Othello’s character that he speaks grandly until this point. As his mind deteriorates, his language becomes less orotund and more like Iago’s. Before falling into a trance, he can’t even command sense and grammar: “Pish! Noses, ears, and lips. – Is't possible? – Confess – handkerchief! – O devil!” When a messenger arrives in Cyprus to call him back to Venice, he responds: “You are welcome, sir, to Cyprus – Goats and monkeys!” Iago corrupts Othello and his language. Othello never recovers, and you can hear echoes of Iago’s coarse, animalistic vernacular in Othello’s final words. Realising his mistake, he tells everyone to add this detail to his legacy:

I took by the throat the circumcised dog,

And smote him, thus. [He stabs himself.]

Funny isn't it, when merely asking a question (sowing a tiny seed of doubt) leads another to destruction?