They’re at it again.

Regular readers of Cosy Moments will remember my review of a recent book about Christopher Hitchens written by Mr Matt Johnson, in which I questioned the Whiggish and Steven Pinkerish portrait of the “Enlightenment.” Staunch advocates of reasonable debate as they are, neither that book’s author nor its publisher responded to my review, but one Mr Adam Wakeling has taken to the web to argue against “the advocates of political Christianity” who argue that “Western civilisation has Christian foundations, and returning to those Christian roots can help protect Western values today.” Mr Wakeling argues against these people, who elsewhere have been called “New Theists”:

But the success of our civilisation rests on the pillars of Enlightenment thought: constitutional government, secularism, science, the rule of law, and human rights—not on belief in the supernatural or in any specific set of ancient myths. In calling for a faithless Christian revival to protect our civilisation, the advocates of political Christianity seem to misunderstand both the nature of that civilisation and of religious belief itself.

In a recent Substack post, Mr Johnson argues that “There’s a straight line from Enlightenment humanism to the liberal rights and freedoms lauded by the New Theists.”

As someone who was a Christian before it was cool, I am pleased if people find a home in church, even if I find their political arguments shallow and predictable. But I am positively allergic to the term “Enlightenment,” – whenever I hear the word, I reach for my pills. What vexes me is the brash confidence with which the label is used. In 1783 the Berlin pastor Johann Friedrich Zollner asked “What is Enlightenment?” and for its online defenders, the answer seems to be “whatever I like.”

Whether they realise it or not, they’re indebted to Peter Gay’s interpretation, in which the Enlightenment is an intellectual programme against religion and for the critical use of reason to spread freedom and progress. Everywhere was in darkness until some clever guys from Britain, France, and Germany wrote a few books to bring light and clarity to the world. For some writers, secularism was the essence of Enlightenment; for others, mental and social emancipation.

But since the 1970s, scholars have realised it’s impossible to speak of the “Enlightenment” as a unity: the writers of the period are far too diverse in their ideas and their styles to neatly fit under one heading – and there isn’t even any agreement about when the period of “Enlightenment” actually began. In the mid-eighteenth century, with the Parisian philosophes? The late seventeenth century, with Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, and Isaac Newton? Even earlier with Francis Bacon, René Descartes, and Thomas Hobbes?

And are any of these figures representative? There is a recognition that writers now dusty and forgotten were actually far more popular in their day than the “great minds” mentioned above. In the age of Alexander Pope, London was full of hacks producing anything they could – travel guides, children’s books, history textbooks, pornography – to make money. Why are these low-grade, commercial writings excluded from the confident summary of the “Enlightenment”?

Messrs Johnson and Wakeling can brazenly claim that the “Enlightenment” is the cause of the liberal democracy they cherish, but such an easy grand narrative has a cost. As I have mentioned before, it’s notoriously difficult to chart the movement of ideas and influences, except in the rare cases when a writer explicitly cites a source. In the cacophonous debates of the eighteenth century, ideas were often stolen, modified, digested, and regurgitated to such a degree that originality is hard to isolate. Hardly any text from this period is definitive or “final,” – each went through a series of drafts, corrections, and editions. The “Enlightenment” tag oversimplifies writers who had complex, wavering, volatile systems of thought that we don’t fully understand or were never consistent to begin with – and once you start categorising writers based on how well they fit into a twenty-first century paradigm, the risk of distortion is huge.

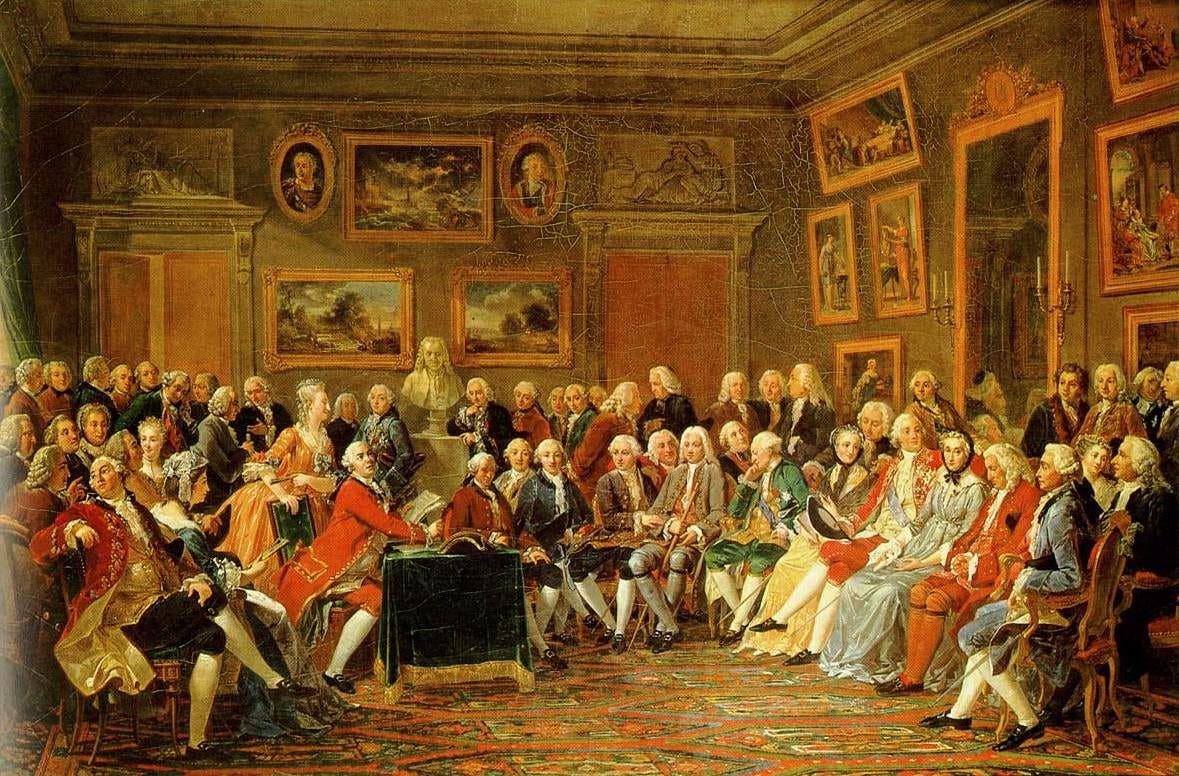

As we know far too well in the age of the web, “the medium is the message,” and any convincing intellectual history must consider the processes of communication and transmission. Books, manuscripts, journals, newspapers, magazines, handbills, sermons, letters, private diaries, and all other kinds of writing were not only means of spreading ideas: they were also physical objects. How did the physicality of these objects affect their circulation and reception? How did they inform discussions in different social contexts – salons, reading societies, private homes, commercial lending libraries, coffee-houses, theatres, and street “soap-box” oratory? Looking at these fields, historians are increasing our understanding and nuance of the “Enlightenment.”

This emphasis on social context might seem out of place, but influences require explanation. Messrs Johnson and Wakeling don’t explain why certain ideas were adopted, or what caused this change of mood they call the “Enlightenment.” If man was now brave enough to renounce his Sky Daddy and think for himself, what were the social, industrial, political, commercial, and familial changes that made this possible? Is it possible that these treasured writers were recording these social changes, rather than causing them?

Although “Enlightenment” thinkers made (according to some) the great achievement of providing a secular alternative to theological viewpoints, they could do so only because of their religious background. The idea of history as a linear development, the division into distinct eras, the idea of the world as a single city, and the vision of a heavenly one – all these elements of eighteenth-century literature are Christian ways of thinking.

In the typical grand narrative, religious ways of thinking were proved by science to be superstition. But the word “science,” invoked by Mr Wakeling, raises problems. In English, the word usually suggests not only a collection of facts but a method which aims observe the world rationally (sometimes while conducting experiments) and publish its findings in precise mathematical terms. Moreover, it strives to remain unbiased and neutral on moral and political issues. But the values of objectivity and neutrality cannot be justified by science; they must be justified by philosophical argument. If Messrs Wakeling and Johnson don’t make this distinction, should we not ask what they mean by “science,” and why many of their “Enlightenment” heroes were not neutral in their promotion of various historical and social studies?

Messrs Johnson and Wakeling are instrumentalising the past to make an argument about the present. They are not alone in doing this. Writing in the aftermath of the Second World War, Horkheimer and Adorno published their Dialectic of Enlightenment, arguing that man gained control over nature and then human beings by “rationally” controlling them with technology. While producing no moral insights, the “Enlightenment” had disenchanted nature and the rest of the world, leaving only problems with rational and objective solutions. But when humans (as they often do) fail to find these objective solutions, the only way to make them see the light is through force. Horkheimer and Adorno argued that the Shoah was a legacy of “Enlightenment” thinking – modern chemistry facilitated the gas ovens, modern railways carried hundreds and thousands of people to extermination camps.

How would Messrs Johnson and Wakeling respond to this famous argument against the “Enlightenment”? Don’t know. If Horkheimer and Adorno’s idea of the “Enlightenment” is tendentious and misleading – as I think it is – then I can’t see why Johnson and Wakeling’s isn’t either.

For online defenders of “the Enlightenment,” far more damning and dilettantish is their exclusion of all but a handful of political and philosophical commentators. During the eighteenth century alone, there were major changes and debates in novels, poems, plays, music, acting, visual arts, architecture, criticism, gardening, and ecology. Wouldn’t an examination of these fields give us a fuller idea of the nature and impact of the “Enlightenment”?

Many philosophes liked music, and many leading composers – Christoph Gluck, Johann Quantz, C.P.E. Bach, Charles Burney – knew the philosophes. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote about music and even invented a system of notation. Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute – in my view the greatest artistic achievement of the eighteenth century – glorifies Freemasonry, which functioned as a sort of international brotherhood to supplement or replace conventional Christianity. So why doesn’t Freemasonry feature in the arguments of those championing “Enlightenment values”?

Because these arguments are not really about the “Enlightenment,” whatever that term means. Like the arts they ignore, like the religions they don’t understand, the “Enlightenment” can’t be reduced to the simple tale of its online defenders. In using the past to substantiate their arguments about the present, Messrs Johnson and Wakeling ignore about fifty years of historical scholarship and present a distorted view of the period they invoke. “Enlightenment,” “science,” “reason,” and “religion,” are not simple objects and cannot be understood except as complex and contingent historical products. If the ideas of the rationalistic Enlightenment could be adopted by Frederick the Great, Catherine the Great, and Joseph II – who were, to put it mildly, not exactly liberal democrats – then why believe that these ideas are the primary cause of twenty-first century pluralistic democracy?

No doubt we all want social cohesion, and to be told that it’s a result of a historical trajectory that starts with the “Enlightenment” might be a nice way to strengthen our commitment to our great intellectual heritage, especially if all we must do is write articles reaffirming our commitment to “constitutional government, secularism, science, the rule of law, and human rights.”

But what about loving your neighbour, giving to the poor, forgiving those who wrong you? That’s much harder. If people are becoming or staying religious for practical and social reasons – as happened a fair bit during, umm, the Enlightenment – then maybe it’s because they find little value in glib solutions based on misreadings of the past.

in Europe instead of 'Enlightenment' the term Renaissance is (also) used, referring to a period where parts of Medieval societies were slowly achieving greater prosperity, even peace, after the devastating Crusades and long, long years of vicious religious wars, including the Spanish Inquisition. we're talkig 14th century Northern Italy, from which these ideational changes were to spread north- and westwards. more like Erasmus' Humanism Descartes' "I think therefore I am" was a staunch criticism of the Church' coruption and stifling abuse of power in many places.

I also always wonder about the universal Enlightenment values argument: If the Enlightenment set of political views is describing reality and all rationally derived, why haven't more cultures come up with them? Here, my thinking is informed by the work for the fabulous Dr. Alice Evans, whose Substack I cannot recommend enough:

https://www.ggd.world/

Summary of stuff I've learned from her economics and social science research: Ideas like equality and individual liberty (she focuses on gender equality, but still the idea applies across the board) are certainly not universal, and do not magically become ascendant in a society when they get more technology and are richer. Indeed, across the Middle East the opposite has happened: countries have simultaneously become wealthier and their populations better educated, *and* more authoritarian, religious, and sexist. Things that I always thought were universal human values, like that you should *love your spouse,* also most certainly are not universal values, and they again do not become so just because people get richer and more educated and techy.

So, whenever Team Enlightenment gets all excited about how the political and epistemic views they espouse are the religion-free ones, I always wish they would maybe, you know, familiarize themselves a little bit with how those views play out in cultures that have different religious backgrounds.