What art was produced between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance?

The state of New South Wales teaches its pupils about the cultural achievements of Europe following a historical schema that looks something like this:

Ancient Greece

Ancient Rome

BLANK

The Renaissance

I wasn’t a good school student, but I got a similar idea of European history from knighted dons at prestigious universities and influential writers such as the Oxford-educated Christopher Hitchens. The Catholic Church ruled Europe for about a thousand years and smothered all artistic endeavours until something called “The Renaissance” revived the creative pursuits of ancient Greece and Rome. Everyone said it, so I thought it was true.

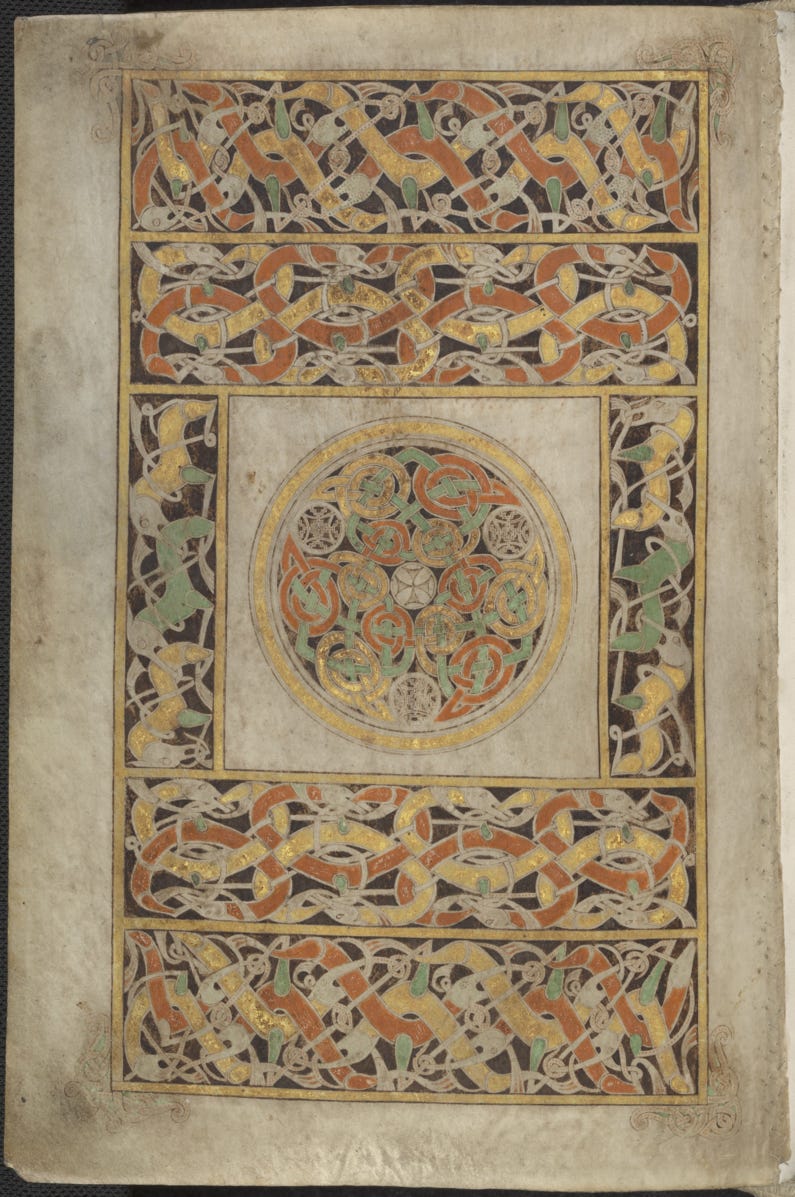

It wasn’t until I visited some great museums in England and Ireland, and saw some pretty impressive evidence, that I started to suspect this neat story wasn’t accurate. I saw things such as:

It wasn’t only the skill and creativity that shocked me: it was also the dates. How were these things produced in the seventh and eighth centuries? Wasn’t that during… the Dark Ages?

And here we see part of the problem: we don’t have a good label for this period, which tries to summarise the thousand-year history of a whole continent. Calling these years the “Dark” ages implies the people of that time were stupid and unskilled, which is clearly false. Calling them the “Middle” ages implies that nothing interesting happened: it was merely a long, dull pause between the more imaginative periods of the classical world and the Renaissance — even the word “Renaissance” (meaning “rebirth”) assumes that creativity died after the fall of Rome and had to be revived by wizards such as Leonardo da Vinci. For this reason, many historians no longer use the word “Renaissance,” preferring the term the “early-modern period.”

The beautiful curlicues above are characteristic of the artwork — found on bone, ivory, stone, weapons, jewellery, manuscripts — made in Britain and Ireland during the seventh and eighth centuries; you could call it the “interlace” period because of the striking and prolific craftsmanship of these designs. John Leyerle argues that you can find similar achievements in the literature of the time. His main example is from Beowulf.

The great cultural achievements that survive the accidents of the past are belittled by the snobbery of the present.

Composed in England some time between the seventh and tenth centuries, Beowulf is preserved on a single manuscript (copied in the late tenth or early eleventh century) now in the British Library. Before the manuscript found its current resting place, it belonged to Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, who kept it (with his other manuscripts) in the inauspiciously named Ashburnham House: in 1731 there was a fire in the library which seared the Beowulf manuscript. We’re lucky the damage wasn’t worse: most Old English manuscripts have been lost, and often the great cultural achievements that survive the accidents of the past are belittled by the snobbery of the present.

An example of Beowulf’s sophistication is how it interlaces narrative “threads.” It withholds Beowulf’s name, first calling him “Hygelac’s thane.” Hygelac is Beowulf’s uncle, and the accounts of his life continually intersect with the main story of Beowulf’s heroism. Hygelac is king of the Geats and is killed in an abortive raid on Frisia. (Unlike some other tales in the poem, Hygelac and his raid are historical.)

The story of the Frisian expedition is broken into four chunks which are placed in the poem without regard for chronology. Far from being artless, this interlacing allows the poet to create contrasts and irony that would have been impossible in a strictly linear narrative. I’ll give you one example: the Queen of the Danes Wealhtheow gives Beowulf some gifts in gratitude after he kills Grendel:

… two arm bangles,

a mail-shirt and rings, and the most resplendent

torque of gold I ever heard tell of

anywhere on earth or under heaven.(Lines 1193 - 1196, Seamus Heaney’s translation)

Without warning or explanation, the poet cuts to Beowulf’s uncle:

Hygelac the Great, grandson of Swerting,

wore this neck-ring on his last raid;

at bay under his banner, he defended the booty,

treasure he had won. Fate swept him away

because of his proud need to provoke

a feud with the Frisians. He fell beneath his shield,

in the same gem-crusted, kingly gear

he was worn when he crossed the frothing wave-vat.

So the dead king fell into Frankish hands.

They took his breast-mail, also his neck-torque,

and punier warriors plundered the slain

when the carnage ended; Geat corpses

covered the field. (1201 - 1212)

The poet trusts that the audience is smart enough to work it out: what a hero earns, a lesser man loses.

Yet these sudden shifts and contrasts also make us rethink Beowulf’s greatness. Mortally wounded by the dragon, he has a final request:

“… I want to examine

that ancient gold, gaze my fill

on those garnered jewels; my going will be easier

for having seen the treasure, a less troubled letting-go

of the life and lordship I have long maintained.” (2747 - 2751)

The king “keenest to win fame” (as the poem calls him) unclasps the “collar of gold” just before he perishes. His death leaves his people vulnerable to attack.

Hygelac dies seeking Frisian gold; Beowulf dies seeking the dragon’s hoard and the glory it will bring. The interlacing structure emphasises the rashness, vanity, and covetousness that persist throughout human history.

This was great, I wanted to read more...

Thanks for this - I am a big fan of Beowulf and like to read it in the dark of winter. I've read it in a few versions, a few times each. Recently I read this version, and LOVED it - she (Maria Davahney Headley)spent years and years translating it for a version that is outstanding https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/08/31/a-beowulf-for-our-moment