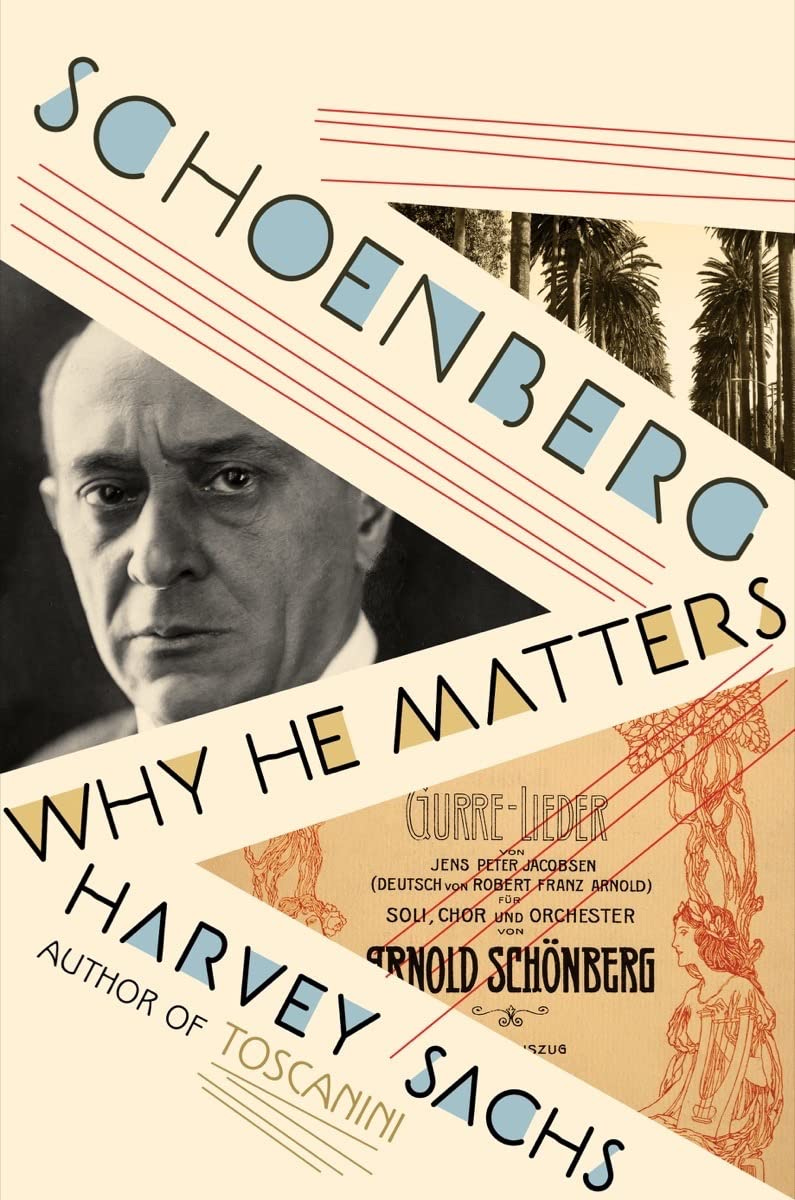

A review of Schoenberg: Why He Matters by Harvey Sachs, Liveright (August 2023)

In the popular imagination, classical music in Europe developed organically from Gregorian Chant until Arnold Schoenberg came along. With his revolutionary compositional techniques, he killed orchestral music and spat on its grave. Some listeners can’t forgive him. Many major orchestras regularly exclude the composer’s works from their programmes. When I was a student in England, I attended classical music concerts 2 or 3 times a week, but I don’t remember any featuring a single Schoenberg piece. It’s a shame – I reckon I would have been perfectly receptive to it: as a teenager, I listened to nothing but heavy metal, so I’m comfortable with music that’s harsh, dissonant, and challenging.

But if you think that Schoenberg’s music sounds like a defective car alarm, then Harvey Sachs’s new book is for you. Rightly sympathetic to his subject, in this short interpretative study Mr Sachs outlines the composer’s major works and the life that inspired them: that of a Jewish boy born in nineteenth-century Vienna (where “even the Jews are anti-Semites”) who flees the Third Reich and ends up in California, where he plays tennis with George Gershwin.

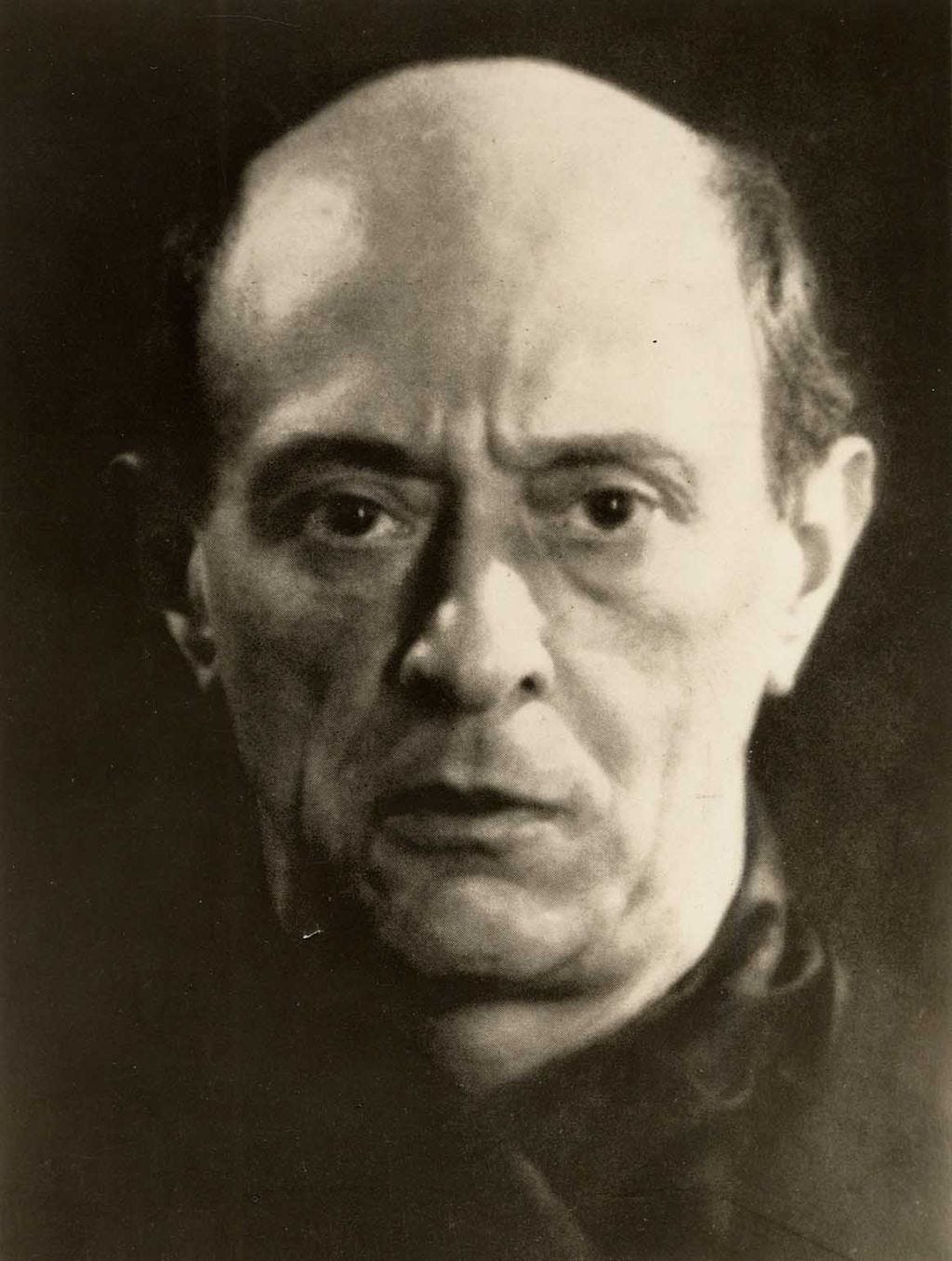

Arnold Schoenberg started playing and composing music when he was eight but didn’t have the prodigious youth associated with composers such as his fellow Wiener Franz Schubert. Only fifteen when his father died, Schoenberg left school and worked as a bank clerk to help support his family. Five years later, he met the conservatory-trained Alexander von Zemlinsky, who got him into an amateur chamber group and introduced him to the music of Richard Wagner. Mr Sachs emphasises that, even this early in his career, Schoenberg considered himself an outsider: first, because of his lack of conservatory training, and second, because he was a Jew.

Yet he was ambitious enough to leave the bank and start a career as a composer. As Mr Sachs rightly emphasises, his first compositions are a continuation of the late-Romantic style he had absorbed in Vienna. Fans of Johannes Brahms, Richard Wagner, and Richard Strauss will hear echoes of those composers in Schoenberg’s early works, none of which is more popular than Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night).

This is the piece that made me fall for Schoenberg’s music. Perhaps overwrought in some sections, it nevertheless has an emotional force and sonorous lyricism that listeners rarely associate with Schoenberg. The lush melodies and adolescent sickliness of late German Romanticism are present, but so are the passages of baffling dissonance that would define the composer’s later works.

The conductor of Vienna’s Court Opera, Gustav Mahler, read the score of Verklärte Nacht and became instrumental in supporting Schoenberg’s career. Schoenberg, his students, Zemlinsky, and Mahler formed a group to challenge the hidebound conservatism of Viennese musical life: one contemporary critic described Schoenberg’s 1903 symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande as “an assassination of sound, a crime against nature.” But while Schoenberg was writing these bold pieces, he told his students to learn from Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms. He had nothing but reverence for the German musical tradition, and knew that the only way to continue it was to revitalise it, not mechanically repeat it.

A great example of this is his extraordinary Kammersymphonie (Chamber Symphony) No. 1, in E Major.

Eschewing the orchestral gigantism of Gustav Mahler’s symphonies and Richard Strauss’s later tone poems, Schoenberg wrote a slimmer, pithier work. Its premiere in 1907 provoked insults and derision. Mahler championed the music, but later admitted that he didn’t understand it: “but [Schoenberg’s] young and perhaps he’s right. I am old and I daresay my ear is not sensitive enough.” (Mahler was forty-six at the time; Schoenberg thirty-two.)

Despite its harmonic and technical challenges, Schoenberg’s first Kammersymphonie fits in the tradition of German functional harmony, the conventional way of thinking about the movement of chords and the relationships between them.

You can’t say the same for his Second String Quartet, written in 1908. (During this time his wife Mathilde was having an affair with their friend and neighbour Richard Gerstl. Some commentators think that the shock caused the emotional turbulence of the piece, but Arnold Schoenberg had mostly finished writing it before he discovered the infidelity.) The quartet – which features a soprano in the last two of its movements – is based the poetry of Stefan George, including the line “I feel air from another planet.”

And it’s here we should see Schoenberg as a musical explorer or astronaut, rather than the head of a gang of vandals. He was continuing the harmonic voyage that his German predecessors (Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner) had started. The older composers sought newer and stranger ways to move from one chord to another and from one key to another. In the Second String Quartet, Schoenberg basically renounced the idea of a tonal centre. The individual parts proceed whether or not they develop traditional harmonic progressions. The dissonances don’t lead to a “home” chord.

Why? In Schoenberg’s view, traditional tonality had exhausted itself: other composers should have realised this, but only he was brave enough to discard the now-flaccid conventional tonalities and venture unencumbered into new land. (Modesty was never Schoenberg’s strength.) Yet Schoenberg continually asserted that he was extending the work of his predecessors, not ending it.

And he was right. Listen to the fourth movement of the Second String Quartet: yes, it’s abrasive, demanding, caustic. But how could anyone continue the overripe richness of late German Romanticism without descending into kitsch? Schoenberg was saving music from banality. His innovations allowed for newer and more challenging forms of musical expression – but the audience’s idea of expression was to hiss and laugh at the premiere.

Despite witnessing some triumphant premieres of his work – such as the one for Pierrot Lunaire – Schoenberg was never warm with his audience: “The artist never has a relationship with the world, but rather always against it,” he wrote, “he turns his back on it, just as it deserves.” Amid worsening relationships between composer and public, in 1918 Schoenberg and his disciples (including Alban Berg and Anton Webern) founded the Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen, Society for Private Musical Performances. Aiming to advance contemporary music, these recitals were open only to subscribing members and were protected from harmful forces like commerce and the press.

Yet a much more harmful force was gaining strength at this time. In the summer of 1921 Schoenberg took his family and some students to Mattsee, a village north of Salzburg. Shortly after their arrival, the local council put up a sign “suggesting” that all Jews should leave. Initially outraged, Schoenberg would later remark with bitter irony that the German music world would simply have to accept that its newest musical genius was a Jew: “Because through me alone and through what I produced on my own, which has not been surpassed by any nation,” he wrote, “the hegemony of German music is secured for at least this generation.”

What Schoenberg had produced on his own was an influential “twelve-tone” system, sometimes called “serialism.”

To oversimplify: in opposition to traditional harmony – which often has one note as its “centre” or “home,” to which all other notes and chords gravitate – Schoenberg’s system tried to emancipate music by repudiating hierarchy and making all twelve notes equally important. It’s not a system where “anything goes,” but one demanding strict logical order and organisation, of which the main result should be comprehensibility. Schoenberg was either laughably naïve or supremely arrogant to think that his twelve-tone system would produce works comprehensible to the average listener. Even today, a century after their composition, audiences find them hard to stomach. But Schoenberg could have written nursery rhymes and the Nazis would have classified his music as “degenerate.” He was a Jew. After Hitler assumed power in 1933, the fifty-nine-year-old Schoenberg boarded a boat with his wife and daughter and headed to New York.

The Yanks liked him more than the Europeans did. He started teaching on the East Coast but a year later moved to California, where he taught several Hollywood composers and Jackie Robinson, who broke the baseball colour line. Schoenberg was grateful to be in America, but missed the cultural environs of Europe. He devoted a lot of time, energy, and cash helping Jews escape Nazi-occupied lands, writing letters of recommendation trying to persuade potential American employers to offer jobs to immigrant musicians. He wasn’t always successful, and we should remember those who couldn’t escape. He kept composing as best he could, but by the 1940s his health started deteriorating while he was appalled by the “amoral, success-ridden materialism” he found in California. Extremely superstitious, he died on Friday 13, July 1951. The New York Times printed his obituary on the front page, and many at the time predicted that his music would eventually be accepted by the wider listening public.

Were their predictions right? Mr Sachs doesn’t think so. In the epilogue, he writes that Schoenberg “wanted his music to be heard and enjoyed by the same people who listen to and enjoy Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, whether or not they can read a musical score. For the most part, this has not happened.”

This is where Mr Sachs’s book is at its most interesting. Besides his brilliant compositions and musical developments, Arnold Schoenberg matters because he raises questions difficult enough to merit books of their own. He spurned popular tastes and became salty when people didn’t like his work.

Now that most composers make money from government grants and university positions, they’re far less beholden to the tastes of their audiences. Does this liberate them, and allow them to follow their instincts, or does it confine them to writing obscure pieces accessible only to fellow composers? Schoenberg didn’t want his audiences to be concerned with music theory, but is such knowledge necessary to enjoy contemporary classical music? On the other hand, can a composer deliberately write for a popular audience without becoming a sell-out?

I’ve avoided talking about the religious aspects of Schoenberg’s music because in my next piece I’m going to write about why one of his operas is essential listening for anyone interested in religion or popular culture. Don’t miss it.

Excellent review - well done!

Sorry for posting irrelevant msg here (I dont know how to send dm on substack)

Have you learned Latin? I am trying to teach myself Latin but I dont know which books to choose...