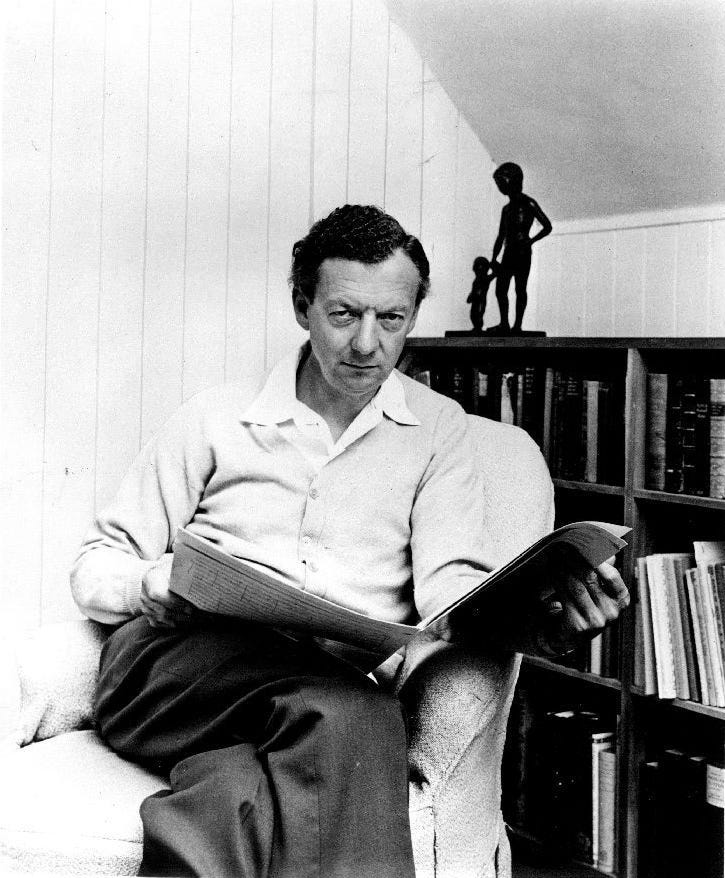

Early in 1950, just before Benjamin Britten started working on his opera Billy Budd, he hired a servant. On a winter night, in a house by the sea, the servant went mad. He clanged at the piano, thinking he was the great composer and Britten his aide.

This small detail exemplifies the eerie quality of many of Britten’s vocal works, especially his setting of Henry James’s 1898 novella The Turn of the Screw. In it, a young, idealistic governess is put in charge of a beautiful English country estate called Bly. With the help of the housekeeper Mrs Grose, she’s to look after the two innocent young children (of “angelic beauty,”) Miles and Flora, on the condition that she never contact their uncle and guardian, a wealthy bachelor living in London. The cosiness of the place is disturbed by the ghosts of two previous employees: Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, the former manservant and governess. The new governess tries to protect the children from the ghosts but ultimately fails, resulting in Miles’s sudden death in her arms.

There are two common interpretations of the novella:

The ghosts are real.

The governess hallucinates the ghosts, which might symbolise her repressed sexual desire for the guardian.

Most readers might be familiar with a similar situation in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. For the first part of the movie, Jack Nicholson hears voices. Alright, you say to yourself, he’s going mad. Or maybe it’s a symbolic representation of alcoholism. Either way, it’s a part of a recognisable world.

But things change after his wife locks him in the pantry. He still hears the voices but then they unlock the door from the outside. This is not something familiar. We’re in a different world. Arguing, as some commentators do, that James’s governess is delusional robs the story of its conflict between normality and strangeness, the orderly and the uncontrollable.

As Hamlet reminds us, there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy. Stories of ghosts and monsters – horror stories – remind us that we, as humans, are limited. There are things we can’t control. There are things greater than us, independent of us – things that threaten us. What the best of these stories do is remind us that these things can reside even in our own minds. It’s possible that the ghost, monster, and gothic stories from the nineteenth-century are a result of that period’s social and religious doubts; something else was needed to remind people of their limitations.

Ghosts and monsters often represent the things that came before us – the evils that must be cleared from the land (or appeased) before civilisation can start. Peter Quint and Miss Jessel are the spirits of Bly, the genii loci, guarding their terrain. They’re servants turned masters; their literary antecedent is Coleridge’s lesbian vampire Geraldine. Quint first gazes at the governess with a “bold hard stare.” Later, he gazes at her through the window with a look “deep and hard.” Miss Jessel is “dark as midnight in her black dress, her haggard beauty,” and rises from the lake a “pale and ravenous demon.” Peter Quint and Miss Jessel are types of the evil eye.

Usually, one combats menacing spirits or propitiates them through prayer. Yet, in The Turn of the Screw, there’s prayer, no hero, no Luigi with a vacuum. The only man in the story (other than the ghost Peter Quint) is the guardian-uncle, far away in London. The one to confront the horror is the young, idealistic governess, who hesitates before sending a letter to the children’s uncle – hardly a wise priestess or Amazonian warrior.

If the ghosts are related to her sexual desires, that would explain why she struggles to banish them. Although the naïve advocates of free love will tell you otherwise, sexuality is often daemonic (think of the sexy Satan outfits you find in costume shops). The idea was prominent in the late Romantic period: in Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (published 1891), and Thomas Mann’s astounding novella Death in Venice (1912), the beautiful boy destroys his admirers and is indifferent to their suffering. (Britten’s last opera was a version of Death in Venice.)

Britten’s operas go further than their sources in emphasising the daemonism, violence, and destruction associated with homosexual yearning. In Billy Budd, the beautiful sailor Billy loves all, while Captain Vere hides his love for him. The master-at-arms John Claggart’s desire for Billy remains unspoken. It festers inside him and turns to hatred, a passion to destroy what he cannot have.

His aria starts as a hymn (“O beauty, o handsomeness, goodness!”) but has one of the most chilling lines in English opera: “Alas! A light shines in the darkness, and the darkness comprehends it, and suffers..."

Claggart ends, “I will destroy you.”

(E.M. Forster, who co-wrote the libretto, wanted Braggart’s aria to be even more intense, “a sexual discharge gone evil,” but was overruled by Britten.) Claggart falsely accuses Billy of inciting a mutiny. Billy kills Claggart and is subsequently executed.

E.M. Forster wanted it to be “a sexual discharge gone evil.”

In The Turn of the Screw, however, the admirer is undead while the beautiful boy is destroyed. In James’s novella, Peter the Poltergeist (okay, fine, I’ll call him “Peter Quint”) is mysterious and associated with uncanny silence. In Britten’s opera, he sings seductively to Miles, accompanied by the ethereal, otherworldly celesta. His opening cadenzas suggest a refinement and sophistication that make him seem more wicked.

Mrs Grose tells the governess about the former valet: “I saw things elsewhere, I did not like, when Quint was free with everyone, with little Master Miles… hours they spent together.” She adds, Quint “had ways to twist them round his little finger. He liked them pretty, I can tell you, Miss, and he had his will morning and night.”

In response, the governess asks, “I know nothing of this place. Is this sheltered place the wicked world, where things unspoken of can be?”

The English country house, usually a haven of comfort and security, is invaded by irrational, daemonic forces.

People, this is not the place for an Airbnb.

In a scene absent from James’s novella, Miles revises masculine Latin nouns (many of them slang sexual terms) and recites a rhyme to help him remember the meanings of the word malo: “malo, than a naughty boy / malo, in adversity.”

Later, in maybe the creepiest part of the opera, Quint sings, “The hero highway man, plundering plundering plundering the land… In me secrets, half-formed desires meet. I am the hidden life that stirs when the candle is out.”

At the start of Act 2, Peter Quint tells Miss Jessel he’s found an obedient follower who will “feed” his “mounting power.” This is the vampire as a gay, paedophilic ghost. He continues, adding a line (not in James) from W.B. Yeats’s poem “The Second Coming,”

“then to his bright subservience I’ll expound the desperate passions of a haunted heart, and in that hour, ‘the ceremony of innocence is drowned!’”

In the last scene, Peter Quint becomes more assertive, telling Miles to stay away from the governess: “Miles, you’re mine! Beware of her!” Miles finally responds, “Peter Quint – you devil!” before expiring in the arms of the governess.

When she realises Miles is dead, the theme from his “Malo” song returns in the clarinet and flute before the governess sings it in despair. Her last note is a G, which sits uneasily with the opera’s final A major chords: an unsettling resolution.

“I am the hidden life that stirs when the candle is out.”

Much of the scholarship about Britten mentions his sexuality, which is frustrating for those who want to understand his music. But I think it’s impossible to ignore his erotic weaknesses when discussing The Turn of the Screw.

Everyone has some anxieties about their personal lives, and often they’re expressed in art. What troubled Britten was not his homosexuality – he never hid his loving relationship with Peter Pears, which lasted more than half his life – but his desire for underage males, a desire so profound a whole book was written about it.

Like many precocious Englishmen of his period, Britten (who composed “The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra,”) remained a child long into his twenties: he was fascinated with the innocence of his schooldays and kept using schoolboy slang while an adult. (This is how he explained his ability to write for children: “It's because I'm still thirteen.”)

In 1942 the poet W.H. Auden (another overgrown child) wrote a letter to Britten which cited the composer’s “attraction to thin-as-a-board juveniles, i.e. to the sexless and innocent,” and continued:

“If you are really to develop to your full stature, you will have, I think, to suffer, and make others suffer, in ways which are totally strange to you at present, and against every conscious value that you have...”

Britten soon cut his relationship with Auden (he refused to meet Auden when the poet visited England in 1953) but that letter from 1942 would later become famous for its prescience. Less often noted is a poem Auden dedicated to Britten, which the composer later set to music:

Underneath an abject willow,

Lover, sulk no more:

Act from thought should quickly follow.

What is thinking for?

Your unique and moping station

Proves you cold;

Stand up and fold

Your map of desolation.

In case this first stanza urging Britten to act on his sexual feelings wasn’t clear enough, the second stanza ends: “Strike and you shall conquer.”

Whom did Britten strike?

Rehearsing for the premiere of The Turn of the Screw in Venice in 1954, Britten became infatuated with David Hemmings, the twelve-year-old playing Miles. Hemmings later attested that, even though he and the composer slept in the same bed, nothing openly sexual happened. (“I have slept in his bed, yes, only because I was scared at night…” Hemmings said later, adding, “and I have never, ever, ever felt threatened by Ben at all because I was more heterosexual than Genghis Khan!”)

After Hemmings’s voice broke, Britten cut all contact with him. (If only there were a way to retain a boy’s angelic high voice. Oh, wait…)

Britten befriended (if that’s the right word) many boys over his lifetime, but only one spoke ill of him: in 1937 the 23-year-old composer met Harry Morris, aged 13. Many years later Morris told his family that he had to repel Britten’s advances by screaming and hitting him with a chair. Britten never tried to do anything like that again.

In A Rhetoric of Motives literary critic Kenneth Burke argues that the struggle of James’s governess is not literally sexual but ambiguously sexual because sexuality is “surrounded by mystification.”

If this applies to James’s novella, then it applies tenfold to Britten’s opera and the composer himself. When Britten’s governess realises she has failed to save the children, she remarks “there is no more innocence in me.”

Nor in the listener. The renewed scholarly interest in pansychism shows that the philosophers are rediscovering what the writers and composers never forgot: consciousness isn’t limited to humans, and is probably much darker than we realise.

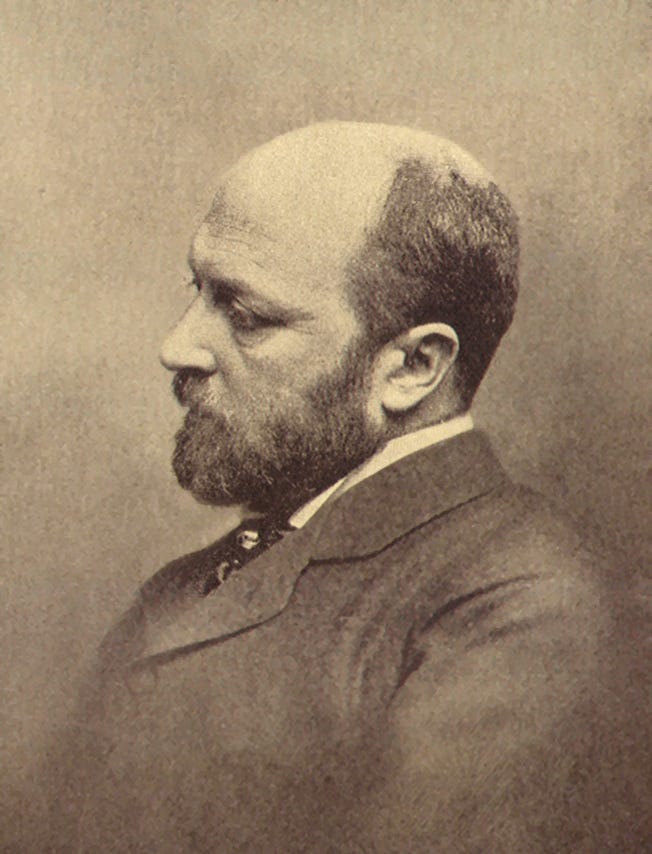

The great critic Edmund Wilson thought that the celibate Henry James identified himself with his female characters:

“There was always in Henry James an innocent little girl whom he cherished and loved and protected and yet whom he later tried to violate, whom he even tried to kill… The maiden innocent of his early novels comes to life again; but he now does not merely pity her, he does not merely adore her: in his impotence, his impatience with himself, he would like to destroy or rape her. The real dramatic and aesthetic values of the stories that he writes at this period are involved with an equivocal blending of this impulse and an instinct of self-pity.”

Is there a similar identification between Britten and Miles, the beautiful precocious schoolboy? Or between Britten and Quint: the older man lovesick in the presence of beatific youth? Or even between Britten and the governess, who smothers the children with attention but can’t protect them from the evils of adulthood? The opera is surrounded by mystification.

There’s a reason Britten’s mad servant bashed chords on the piano while noone listened but the sea. Preceding language and logic, music is probably the artform best suited to expressing the phantoms that lurk in the country houses and the desperate passions of a haunted heart.

Wow! So much to digest. What a great article!!