As a Sydneysider, the only thing I knew about Western Australia was that it was big and that its swans were black. Having visited Perth a couple of times, I can now appreciate its quiet, its remoteness, its horizon that expands to reveal the Indian Ocean and the promise of mysterious lands beyond. Even for Aussies, the west coast is exotic.

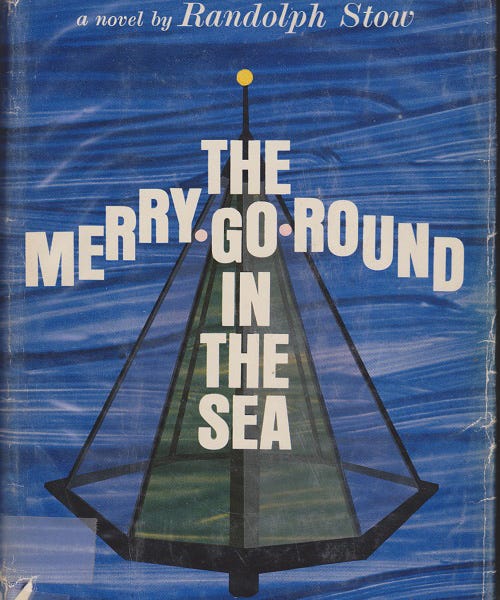

This is true even for people who live there. About 260 miles north of Perth is a city called Geraldton, the birthplace of Randolph Stow and the setting of his semi-autobiographical novel The Merry-Go-Round In The Sea. It describes two merry-go-rounds: one in the sea (actually the mast and wires of a wrecked barge) and one on the foreshore. The novel opens with a description of the foreshore merry-go-round:

The merry-go-round had a centre post of cast iron, reddened a little by the salt air, and of a certain ornateness: not striking enough to attract a casual eye, but still, to an eye concentrated upon it (to the eye, say, of a lover of the merry-go-round, a child) intriguing in its transitions. The post began as a square pillar, formed rings continued as a fluted column, suddenly bulged like a diseased tree with an excrescence of iron leaves, narrowed to a peak like the top of a pepper pot, and at last ended, very high in the sky, with an iron ball. In the bulge where the leaves were, was an iron collar. From this collar eight iron stays hung down, supporting the narrow wooden octagonal seat of the merry-go-round, which circled the knees of the centre post rather after the style of a crinoline. The planks were polished by the bottoms of children, and on every one of the stays was a small unrusted section where the hands of adults had grasped and pulled and sending the merry-go-round spinning.

Apparently the first Geraldton foreshore merry-go-round was erected in 1921, but in 1988 a replica was built to commemorate Stow’s novel. His poem “Merry-go-round” was read at the opening:

This is the playground circumnavigation:

The leap in space and safe return to land,

Past sea and hills, boats, trees, familiar buildings,

Back to the port of one assisting hand.Adventurers learn here; but do not venture

Yet from their circular continuous sweep

From start to start. Where going is home-turning

Nothing is lost, what’s won is all to keep.

The gulls stoop down, the big toy jerks and flies;

And time is tethered where its centre lies.

Play is the start of an adventure where everyone returns home triumphant.

But the governors saw it another way. In 2010 — the same year that Stow died — the local council decided that, in the interests of safety, the merry-go-round should be bolted down to prevent it from spinning.

Despite its reputation as a carefree country, Australia is a bureaucrat’s paradise. In The Merry-Go-Round In The Sea, this is what Rick complains about after returning from the Second World War:

“I can’t stand… this – ah, arrogant mediocrity. The shoddiness and the wowserism and the smug wild-boyos in the bars. And the unspeakable bloody boredom of belonging to a country that keeps up a sort of chorus. Relax, mate, relax, don’t make the peace too hot. Relax, you bastard, before you get clobbered.”

His outburst is striking, considering that he earlier quotes these lines from Donne, expressing that his home is his solid base of support despite his wanderings:

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes me end where I begun.

But Rick (like Stow himself) doesn’t end where he began. Like many Australians seeking creative and professional opportunities, he goes to England. Rick’s emotional life foreshadows that of the literal merry-go-round in Geraldton. In Australia, he’s bolted down. The country’s wide-open plains are empty: he has elbow room but nothing to do. Stow captures this feeling in a painful scene where Rick proposes to a young lady, Jane:

“I want to be young,” he said, low. “I don’t seem to have had the chance. No, that’s not right. I don’t seem to have taken the opportunity.”

“Can’t you be young with me?”

“It’s four years,” he said, turning to look at her, “since Hughie and I came back from the war. And oh God, Jane, if you could imagine what sort of life we’d imagined for ourselves. Heroic lives. And what came of all that? Hughie sits in his little suburban house listening to the wireless and I swat for a career that bores me stiff in anticipation, and somewhere out in the big wide world people younger than me are getting everything out of life that I promised myself that I was going to have as soon as the war stopped. I’m too young to rot. Not very young, but too young for the suburbs.”

After she rejects his marriage proposal and slams the door on him, he “felt even then a shamed sensation of release. On the blue river white yachts were moving, and the river flowed to the blue sea, which flowed everywhere.” Unlike the expansive vistas of the land, the sea is an image of endless possibilities.

But it’s not only Rick who wants to escape. The novel’s first chapter ends with the six-year-old Rob and his impossible desire to flee the vicissitudes of life:

He would swim and swim miles and miles, until at last the merry-go-round would tower above him, black, glistening, perfectly rooted in the sea. The merry-go-round would turn by itself, just a little above the green water. The world would revolve around him, and nothing would ever change. He would bring Rick to the merry-go-round, and Aunt Kay, and they would stay there always, spinning and diving and dangling their feet in the water, and it would be today forever.

Representing adventure for Rick, the sea for Rob implies calm and stability. But even he senses that the endless movement of the ocean suggests the unstoppable progress of time and the threat of war marching south: “Each winter the sea gnawed a little from the peninsula. Time was irredeemable. And far to the north was war.”

Dangerous and enigmatic, the sea is an ancient literary symbol. Perhaps better than anyone else, Australians know its risks. Walking home from school, Rob and his buddies discusses which branch of the Forces they would join. The image here is one of simultaneous industrial and natural hazards:

Donny Webb was going in the Navy. He thought of Donny disfigured with burning oil, watching the dark fins of sharks come closer. Sharks were so commonplace, so likely. Rob could not admit to Donny he was afraid of the sea.

Even in the idylls, even in the remotest parts, there is no escaping pain or death. Et in Arcadia ego.

Nevertheless, Rob is drawn to the sea:

He plunged into the clean sea, skimming the sand and weed of the sea-floor, wanting to stay down there, wondering what it was like to drown among the trailing ropes of watery light.

Although this could reflect Stow’s personal life (he attempted suicide) it does illustrate that some young men are attracted to danger. A man’s fight for survival (against the natural world, against other men) can start his emotional development and maturity.

But just as often it can do the opposite: Rick returns from war with what was once called shellshock and is now insipidly called PTSD. As a result, he can’t connect to people within his own town. Even without such trauma, Rob’s father is the typically distant Aussie dad:

The boy rather liked the look of his father, who was tall and had a face like the King. Watching him from a distance he decided that his father was probably a nice man. But they kissed one another with great reserve, and had nothing to say.

Rick departs at the end of the story, leaving Rob without a male guide. Rob’s quest for maturity remains incomplete, his pastoral dream of playful adventure ruined. All he’s left with in suburban Australia are empty promises and imitations:

The boy stared at the blur that was Rick. Over Rick’s head a rusty windmill whirled and whirled. He thought of a windmill that become a merry-go-round in a back yard, a merry-go-round that been a substitute for another, now ruined merry-go-round, which had been itself a crude promise of another merry-go-round most perilously rooted in the sea.