You’re right: I was asking for it.

I suppose I can’t write an article titled “Shut Up About The Enlightenment” and then be disappointed when my opponents don’t respond.

Still, one longs for clarification. In his Quillette essay about the “New Political Christianity,” Adam Wakeling writes, “The Bible says that God created man in his own image, but it also endorses killing religious dissidents, sacking and plundering cities, and taking women as sex slaves.”

Mr Wakeling’s prose is clear, but his argument is not. Is it that the Bible can’t be a source of timeless wisdom because it so clearly reflects the historical context it was written in? Is it that Christians can’t have religious reasons for objecting to immorality? Is it that the Bible is valueless because it contradicts itself? Don’t know.

That the Bible is a source of wisdom for believers and atheists alike should be obvious. Only an oaf or a libertarian would deny it. In any case, Mr Wakeling could improve his argument by acquainting himself with what many Christians actually believe.

What Mr Wakeling calls “the Bible” is a compilation featuring books of different genres and purposes. Referring to this collection as a singular – the Bible, Scripture – has its uses but obscures that these texts became prominent in Jewish and Christian communities only because of historical accidents and the predilections of various compilers and editors. The canon was never fixed. What qualifies or disqualifies a piece of writing as Scripture owes as much to social, political, and historical factors as it does to theological ones.

Doesn’t this desacralize the Bible? Not at all. Peter Enns offers an analogy: just as Christ is both God and human, so is the Bible. It was connected to the ancient cultures who produced it and spoke to them in idioms they could recognise. If you think of a muse singing through Homer or Milton, then you can adopt the perspective that all literature is a collaboration between divinity and humanity. It would be incomprehensible otherwise.

What, then, of the evil described in these texts? Jews and Christians have long known that the biblical canon itself is a combination of parts sacred and unseemly, so that a literal reading of it would attribute immorality to God. As I mentioned in my first instalment, Mr Wakeling pays no attention to how certain ideas are received within a community. Does any priest read out passages from the Old Testament and say, “There you have it: enslave your neighbour”? Many of the faithful will acknowledge that there are differing degrees of inspiration in their canonical texts; Mr Wakeling only has to attend an Anglican, Catholic, or Orthodox liturgy to realize that the Gospels have a special prominence for Christians.

Furthermore, Christians have not always trusted every canonical text on every topic: the books of Job and Ecclesiastes deny the existence of the afterlife and the possibility of resurrection, but they remain in the canon because they offer wisdom on other matters. In any case, Jews and Christians will reinterpret or reject anything that seems unworthy of God.

It's not because they’ve adopted Enlightenment ideals, as Mr Wakeling suggests.

The God that Christians, Jews, and Muslims worship is not only the biblical god, either in his component parts (El, YHWH, and other Levantine deities) or his later, composite form. The God of the Abrahamic religions includes that biblical material, but also divine concepts understood by Neoplatonist philosophers such as Plotinus, Porphyry, Iamblichus, and Proclus.

One of their contributions comes from a question introduced in Plato’s dialogue Euthyphro. The so-called Euthyphro Dilemma asks: "Is something good because God commands it, or does God command it because it’s good?" In other words, is morality defined by divine command, or is there a higher standard of goodness that even God follows? If the first, then God rules not by wisdom but by power; goodness is not a meaningful category and morality is simply following orders. If the second, God is not really good but only conforming to the source of what’s good. Euthyphro doesn’t reach the solution the Neoplatonists did after reading and harmonising all of Plato’s works: God is the good – the source of reality is also the source of goodness, beauty, truth, unity.

Hellenistic Jews and Christians adopted this insight as well as the allegorical reading of Homer that was popular in Alexandria. There, Greeks developed an allegorical way of reading the epic poems that allowed them to reinterpret the questionable actions of the gods in a way that was morally and metaphysically agreeable.

This shouldn’t be surprising. We’re used to such analysis: the internet is awash with commentators arguing that Star Wars is really an allegory for American imperialism, or that Nelson’s Column is really a monument to the enduring power of the almighty phallus. What surprises people like Mr Wakeling is that ancient Jewish and Christian exegetes weren’t slouching troglodytes. Studying the ancient commentators, you’ll find that there are not only inspired writers but also inspired readers.

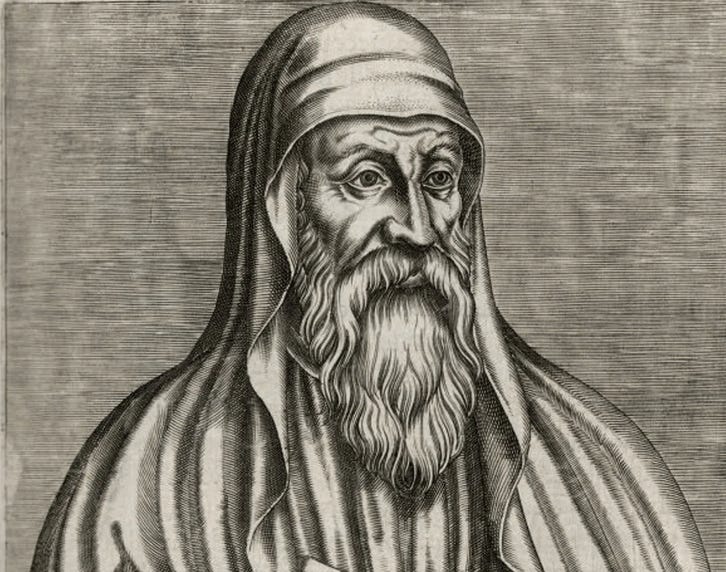

Chief among these is Origen of Alexandria. In his book On First Principles, he suggests that there are three levels of meaning in Scripture, reflecting the body, soul, and spirit in a human being. Although Origen rarely explicates all three levels of meaning in his commentaries, his point is that the meaning of any given passage is not always self-evident, and that the Holy Spirit actually included “stumbling blocks” and “obstacles and impossibilities” so that readers become conscious of the deeper, spiritual meanings found in the scriptures:

Now the Holy Spirit took care of all this, as we have said, in order that, when those things on the surface can be neither true nor useful, we should be recalled to the search for that truth demanding a loftier and more diligent examination, and should eagerly search for a sense worthy of God in the scriptures that we believe to be inspired by God. (Translation by John Behr.)

Origen also applies this method to the New Testament:

And anyone who has read carefully will find in the Gospels many instances… from which he will note that in those narratives, which appear to be recorded according to the letter, there are inserted and interwoven things which are not accepted as history but which may hold a spiritual meaning.

How did Origen recognise the contradictions, the slaughters, the historical impossibilities of the Bible? Writing in the early third century, he must have been influenced by the Enlightenment! He read Sam Harris and Steven Pinker!

The best example of a sustained allegorical reading in a Christian context is probably Gregory of Nyssa’s Life of Moses. The second chapter of Exodus says that:

And it came to pass in those days, when Moses was grown, that he went out unto his brethren, and looked on their burdens: and he spied an Egyptian smiting an Hebrew, one of his brethren.

And he looked this way and that way, and when he saw that there was no man, he slew the Egyptian, and hid him in the sand.

This is quite awkward for the faithful. How does Gregory of Nyssa interpret it?

The fight of the Egyptian against the Hebrew is like the fight of idolatry against true religion, of licentiousness against self-control, of injustice against righteousness, of arrogance against humility, and of everything against what is perceived by its opposite.

Moses teaches us by his own example to take our stand with virtue as with a kinsman and to kill virtue’s adversary. The victory of true religion is the death and destruction of idolatry. So also injustice is killed by righteousness and arrogance is slain by humility. (Translation by Abraham J. Malherbe and Everett Ferguson.)

It was figures like Origen and Gregory – insisting that the literal readings of the Old and New Testaments cannot always be historically or eschatologically accepted, that not everything attributed to God in the scriptures can be literally true – who were the most important and influential in the development of the Christian tradition. They defended a Christianity consonant with reason. The Church Fathers (as they came to be known) were working within the broader culture of Greek philosophy.

This is unpleasant news for some: when I was an undergraduate studying Ancient Greek, a few dons hinted that nothing written after 400B.C. was worth reading. On the other hand, the Enlightenment cheerleaders don’t really care to admit that reason existed before the eighteenth century. During the anti-Christian pogroms of the emperor Decius, Origen was tortured on the rack. Denied a martyrdom, he perished a few years later. Many in the church still fail to acknowledge his achievement, his name wrongly associated with heresy. Imagine, after all that, he had to suffer an educated political commentator asserting that the Bible “endorses killing religious dissidents, sacking and plundering cities, and taking women as sex slaves.” Maybe he died at the right time. He doesn’t have to endure what we do: brilliant allegorists being insulted by literal-minded dilettantes.

This is all quite cogent, William. Yes, the people you lambast are shallow and uninformed. But I’m not sure that reason can lead to faith; it is more likely the other way round. I don’t think we can ultimately know why we believe what we believe and perhaps we should just accept that. It might help make pluralists out of us, in the spirit of, say, Isiah Berlin.