In my previous piece about Arnold Schoenberg, I avoided talking about too much music theory because I didn’t want to give the impression that he was a composer of puzzles. I think some of his work is brilliant, but all of it is challenging. His innovations opened the door to new musical expressions, only to have some listeners beg him to close it again.

Generally, listening to instrumental music isn’t confusing because the melodies, rhythms, and timbres still give a sense of narrative. But this is much harder to do in Schoenberg’s twelve-tone musical system: there’s no “home” chord, no sense of direction, and very little repetition. It’s hard to get your bearings. In his opera Moses und Aron, Schoenberg employed the emotional resources of his twelve-tone system and gave his music a discernible structure and narrative by applying it to a text.

At first glance, Schoenberg’s opera sounds like a non-starter. Moses, his main character, has no saucy sex life. So which events did Schoenberg dramatise?

The plagues of Egypt? No.

The parting of the Red Sea? No.

The confrontations with the Pharaoh? No.

To make matters worse, the Scriptures tell us that Schoenberg’s leading man is “heavy-mouthed and heavy-tongued” (Exodus 4:11).

People, this opera should not work.

But it does.

It was originally an oratorio Schoenberg started writing in 1928, when he was thinking seriously about Judaism. The previous year, he completed the agitprop drama Der biblische Weg (The Biblical Way) which, despite the title, is more concerned with politics and psychology. It follows the protagonist Max Aruns (a Theodor Herzl-like character) who tries to establish a Jewish state in Africa.

The focus in Moses und Aron is more on aesthetic and theological problems. An abstract divine truth (“The Voice” from the Burning Bush) presents itself to Moses, whose mission is to communicate it to “The People.” Aron is the intermediary between Moses and the people, but he distorts the message in attempting to make it accessible to them. As a result, they’re misled and fall into idol worship. Moses’ mission fails.

The opera starts with a chorus of a wordless “O” to represent the divine voice. Then Moses cries out to it, “unique, eternal, omnipresent, invisible, and unrepresentable God!”

Catchy.

Moses’ speech impediment is musically expressed through Sprechstimme, a type of speak-singing which Schoenberg pretty much invented (although there were a few precedents): the singer declaims and doesn’t hold the notes. When Moses tells the divine voice that he “can think but not speak,” the voice tells him that “Aron will be [his] mouth.”

Aron is the one to persuade the people. He has a beautiful tenor voice, and the contrast with Moses couldn’t be more obvious. Early in the opera, they confront each other. There’s plenty of sound but no communication. Aron is associated with seductive and charismatic singing, miracles, and finally the idolatrous Golden Calf. These become the means of betraying the divine voice. Schoenberg’s Moses is like Michelangelo’s: cold, stubborn, marmoreal.

Their argument is about the limits of human perception and the impossibility of representing the divine. Moses speaks of a God “not conceived because unseen, can never be measured, everlasting, eternal, because ever present…”

Aron’s depictions, though, are about what can be used for political gain and comprehensibility. How else can he persuade the people?

Moses: How can fantasy thus picture the unimageable?

Aron: Love will surely not weary of image forming!

Aron later asks a pointed question: “can you love what you can’t imagine?” Later, he claims that the people can see God, and some of them start offering descriptions.

Man: The newest god might be stronger than Pharaoh.

Girl: I believe it will be a pleasing god, beautiful and shiny, like Aron.

When Aron asks the people to worship, they ask where Moses is and say they can’t see his God. “But where is he? Show him to us!” Aron turns Moses’ staff into a serpent and performs some other miracles. The people’s desire for spectacle and pageantry comes to a climax in the scene with the Golden Calf.

Here are the stage directions for that scene:

“During Aron’s last speech processions of laden camels, asses, horses, porters and wagons enter the stage from different directions, bringing offering of gold, grain, skins of wine and oil, animals, and the like. At many places in the foreground and background these are herds of all manner of animals pass by.

Simultaneously, preparations for slaughter are to be seen at many places. The animals are decorated and wreathed. Butchers with large knives enter and with wild leaps dance around the animals.

The slaughterers kill the animals and throw pieces of meat to the crowd. Some people run around with bloody pieces of meat and consume them raw. Meanwhile large pots are brought and lit. The sacrifice is brought to the altar.”

Four naked virgins step before the calf:

“The girls hand the priests the knives. The priests seize the virgins’ throats and thrust the knives into their hearts. The girls catch the blood in receptacles. The priests pour it forth on the altar. Destruction and suicide now begin amongst the crowd. Implements are shattered, stone jars are smashed, carts destroyed, etc. Everything possible is flung about: swords, daggers, axes, lances, jars, implements etc. In a frenzy some throw themselves upon implements, weapons, and the like, while others fall upon swords. Still others leap into the fire and run burning across the stage. Several jump down from the high rock, etc. Wild dancing with all this.”

Then:

“A naked youth runs forward to a girl, tears the clothes from her body, lifts her high and runs with her to the altar.”

“Exit toward the background; many men follow this example, throw their clothes aside, strip women and bear them off the same way, toward the background, pausing at the altar.”

Others cry out: “Fertility is holy! Desire is holy!”

Ironically, throughout the opera the people only show collective agreement in their orgy around the Golden Calf. Despite the dense polyphony, the music for this scene is the most accessible part of the work:

On YouTube, you can find many different versions of this scene, some of them quite lurid. We are the ones dancing around the calf.

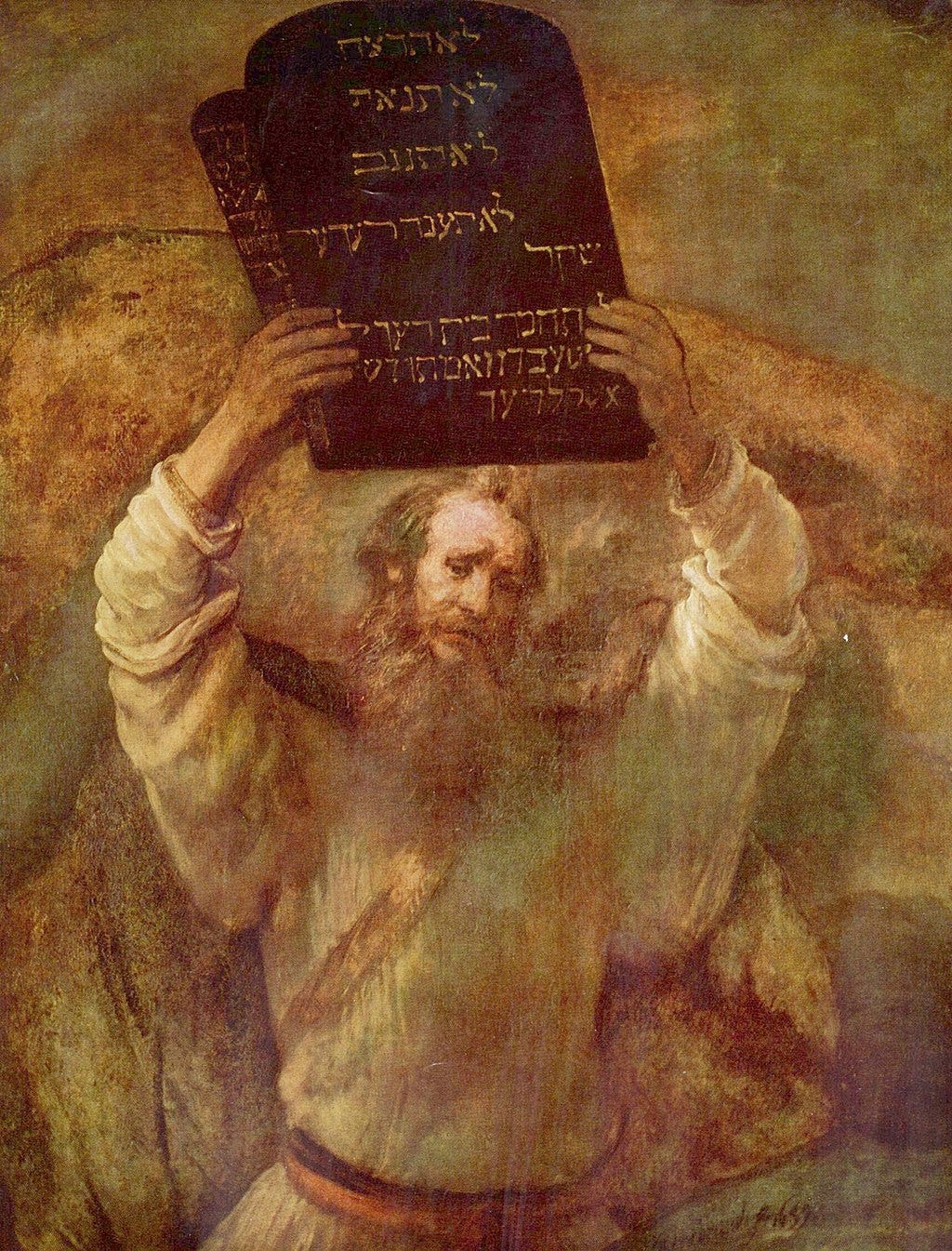

Meanwhile, Moses, atop Mount Sinai, receives the Tablets of the Law. When he returns and asks Aron what has happened in his absence, the latter says he worked miracles before the people’s eyes and ears. He felt compelled to provide an image for them. He points out that the Tablets of the Law themselves are tangible and physical. Moses is devastated. He feels he must smash the Tablets and declare his failure.

Moses ends in despair and defeat: “Inconceivable God! Inexpressible, many-sided idea, will You let it be so explained? Shall Aron, my mouth, fashion this image? Then I have fashioned an image too, false, as an image must be. Thus I am defeated. Thus, all was but madness that I believed before, and can and must not be given voice. O Word, thou word, that I lack!” There’s a long F-Sharp on the violins which builds and then subsides to nothing.

The opera is actually incomplete. Schoenberg wrote a third act but never completed the music for it. In my view, it’s better that he didn’t. Moses und Aron is an extended meditation on the impossibility of fully expressing the sacred. How could it progress after Moses’ failure?

There are some secular interpretations which read the “prophetic” aspects of the opera as expressing the artist’s transcendent expression and the fear of superficiality: as popular music started to become commercial, “pure” music had to remain uncontaminated. On this view, Moses und Aron dramatises the conflict between eternal principles and instant gratification.

It’s an interesting way to view the opera, but Schoenberg continually emphasised its religious and transcendental aspects. In a 1912 essay, he wrote:

“Since music as such lacks a material-subject, some look beyond its effects for purely formal beauty, others for poetic procedures. Even Schopenhauer, who at first says something really exhaustive about the essence of music in his wonderful thought: ‘The composer reveals the innermost essence of the world and utters the most profound wisdom in a language which his reason does not understand, just as a magnetic somnambulist gives disclosures about things which she has no idea of when awake’ — even he loses himself later when he tries to translate details of this language (which the reason does not understand) into our terms. It must, however, be clear to him that in this translation into the terms of human language (which is abstraction, reduction to the recognizable) the essential, the language of the world (which ought perhaps to remain incomprehensible and only perceptible) is lost.”

The main thought here is that the “essential” is inaccessible to reason. Schoenberg would expand on this idea in a letter to the painter Wassily Kandinsky:

“We must become conscious that there are puzzles around us. And we must find the courage to look these puzzles in the eye without timidly asking about ‘the solution.’ It is important that our power to create such puzzles [i.e., artworks] mirrors the puzzles with which we are surrounded, so that our soul may endeavour – not to solve them – but to decipher them. What we gain thereby should not be the solution, but a new method of coding or decoding. The material, worthless in itself, serves in the creation of new puzzles. For the puzzles are an image of the incomprehensible. And imperfect, that is, a human image. But if we can only learn from them to consider the incomprehensible as possible, we get nearer to God, because we no longer demand to understand him. Because then we no longer measure him with our own intelligence, criticize him, deny him, because we cannot reduce him to that human inadequacy which is our clarity.” (My emphasis.)

Maybe we need to keep the puzzle metaphor we started with. The artwork/puzzle brings us nearer to God because it shows us the limits of human perception; we recognise that our “clarity” is our “inadequacy.”

And maybe only an unfinished opera can communicate the idea of an unrepresentable God. In a 1946 essay, Schoenberg wrote that “music conveys a prophetic message revealing a higher form of life towards which mankind evolves.” Like the divine, music is infinite; it can be felt and experienced but can never be fully captured by language or reason.