Below are three extracts written by three different men. I want you to tell me who you think wrote each one, and what you think his religious views were:

“Vaccination is really nothing short of attempted murder. A skilled bacteriologist would as soon think of cutting his child’s arm and rubbing the contents of the dustpan into the wound as vaccinating it in the official way. The results would be exactly the same.”

“If anyone take observation of the stars in order to foreknow casual or fortuitous future events, or to know with certitude future human actions, his conduct is based on a false and vain opinion... On the other hand if one were to apply the observation of the stars in order to foreknow those future things that are caused by heavenly bodies, for instance, drought or rain and so forth, it will be neither an unlawful nor a superstitious divination.”

“Astronomy is not only pleasant, but also very useful to be known… Wherefore, as ingenious men are to be honoured who have expended useful labour on this subject, so they who have leisure and capacity ought not to neglect this kind of exercise.”

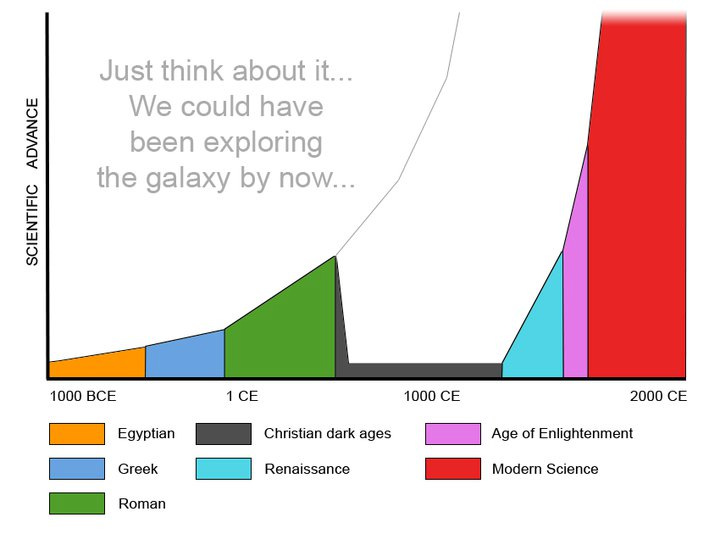

If you’ve been paying attention to popular culture and media, it should be easy to guess the religious beliefs of these writers. A skit on Family Guy shows us a utopian world where “Christianity never existed, which means the dark ages of scientific oppression never occurred, and thus humanity is a thousand years more advanced.”

Everyone knows this is true, even though almost no one can cite a reputable book or article on the subject. The New Atheists exploited and exacerbated this bit of cultural knowledge, and it didn’t seem to matter that they weren’t trained as historians.

(“New Atheist” is a convenient shorthand for the militant anti-religious activists who became famous during their publishing fad in the mid 2000s. The most celebrated “New Atheists” were Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, and A.C. Grayling. What distinguishes them from “old” atheists? Two things: the first is that they were largely a media phenomenon, selling millions of books, and featuring prominently on TV and the internet. The second was their almost complete ignorance of religious, philosophical, and historical arguments.)

The New Atheists have lost their puff, but most of their arguments are uncritically accepted, especially online, where it seems most people now get their information. The following chart is notorious:

With that in mind, I’ll reveal the results of our opening quiz. The authors were:

George Bernard Shaw (atheist)

Thomas Aquinas (Catholic)

John Calvin (uhh, Calvinist)

Surprised? You shouldn’t be. The idea that “religion” is fundamentally opposed to “science” is a common one, known as the Conflict Thesis. The advantage of the Conflict Thesis is that it’s easy to understand, with clearly identifiable villains and victims. The disadvantage of the Conflict Thesis is that it’s wrong.

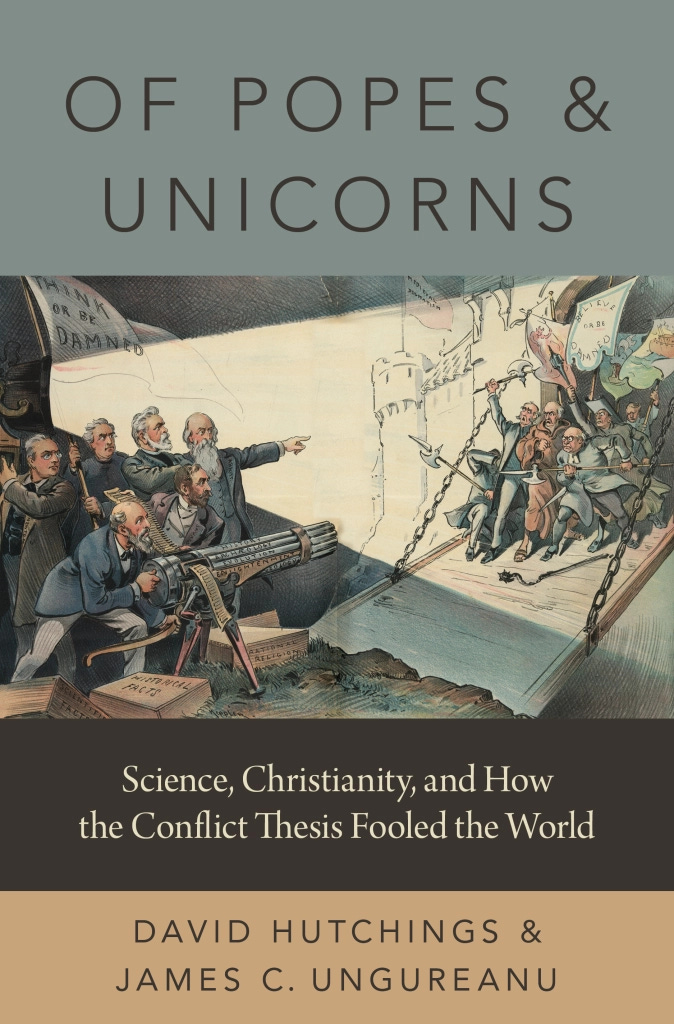

This is the argument of David Hutchings and James C. Ungureanu, co-authors of Of Popes and Unicorns: Science, Christianity and How the Conflict Thesis Fooled the World. Released last year, it was almost completely ignored by the English-language reviewers, who tend to scrupulously avoid anything that might raise the quality of debate about religious and historical topics. (The one exception is my talented and industrious compatriot Tim O’Neill, who runs the very informative website History for Atheists and interviewed the authors on his YouTube channel.)

Of Popes and Unicorns is fun, stimulating, and can be finished within a few hours: it’s intellectual Viagra.

Although there were some earlier polemics (mainly from the French Revolution of 1789) that opposed science and Christianity, the most influential perpetrators of the Conflict Thesis were John William Draper (1811 – 1882) and Andrew Dickson White (1832 – 1918).

If you believe that science and religion are necessarily antithetical, these two dead men have fooled you.

Messrs Hutchings and Ungureanu do a great job of showing you the lives and biases of Draper and White. Draper (author of A History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science) seemed to have a very strong anti-Catholic bias (he was far more lenient towards Protestant and Orthodox churches) whereas White (author of A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom) was involved with some acrimonious disagreements while he was trying to found a non-sectarian educational institute (which eventually became Cornell University).

By showing us the personalities of Draper and White, and the sorts of circles they travelled in, Of Popes and Unicorns shows that the Conflict Thesis is not a universal truth. Rather, it’s the result of two peculiar men and their specific circumstances. Had our authors wanted to write a much larger book, they could have taken this historicising project further and shown that the definitions of “science” and “religion” have changed over time; they are not pure, abstract concepts but are always affected by social, historical, political, technological, and economic factors.

“But William, you dupe!” I hear you shout, “everyone knows that Christians believed the earth was flat until Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan proved them wrong!”

My friend, Draper and White have fooled you.

They both cite the early Christian writers Lactantius (born around AD 245) and Cosmas Indicopleustes (living AD 6th century) who did indeed argue that the world was flat. There might have been a few other Christians who agreed with them. But the vast majority did not. Historians of science note that, during the Middle Ages, the spherical nature of the earth was common knowledge and taught in universities. Even non-scientific works — Dante’s Divine Comedy, Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales — treat the Earth as a globe. Lactantius and Cosmas have had no influence on orthodox Christian thought. Of Lactantius, the online Catholic Encyclopedia writes: “The beauty of the style, the choice and aptness of the terminology, cannot hide the author's lack of grasp of Christian principles and his almost utter ignorance of Scripture.” So where does the idea of Columbus-the-bringer-of-truth-and-light come from? A sensationalised novel by Washington Irving published in 1828.

“But William, you sucker!” I hear you cry, “everyone knows that Christians opposed medicine, pain relief, and the study of anatomy!”

My friend, Draper and White have fooled you.

The “official” Church maxim claiming that it abhors the shedding of blood (ecclesia abhorret a sanguine), looks authoritative because it’s in Latin, but it doesn’t come from any Church document of the Middle Ages. It comes from an eighteenth-century French historian. Of Popes and Unicorns cites Andrew Cunningham, a historian of medicine and an atheist, who wrote that the Catholic Church was never opposed to the practice of anatomy, whether for teaching or research purposes. Historians have not been able to find one case of an anatomist prosecuted by the Church for dissecting a human cadaver. Of Popes and Unicorns also notes that the fiercest opposition to anaesthetic and inoculation came not from priests but from doctors. The quote above from George Bernard Shaw reveals that there’s nothing particularly Christian about opposing vaccination.

“But William, you damn dirty ape!” I hear you roar, “everyone knows that Christians persecuted Hypatia, Giordano Bruno, and Galileo because the Church didn’t like their scientific research!”

My friend, Draper and White have fooled you.

(Well, not only you. They even fooled A.D. Hope, who included these supposed cases of repression in “Advice to Young Ladies,” one of the most powerful Australian poems of the twentieth century.)

It appears, like the early Christians, the apostles of science see themselves as ridding the world of superstition, and have their own martyrs who died for the cause. Apparently, Hypatia of Alexandria was a brilliant atheist and mathematician. Apparently, she was torn apart by a Christian mob. Apparently, the Christians killed her because they hated what she was teaching.

One problem with this story is that almost none of her work survives, which makes it hard to say with confidence that she was a brilliant anything. She probably worked with her father Theon, who was a renowned mathematician, but he also studied divination and auspices; he wrote a (lost) work about interpreting (among other things) the croaking of ravens.

The idea that Hypatia was anything like a modern scientist is ludicrous. The idea that she was killed because she was an atheist or because Christians were anti-science is equally absurd. As our authors put it, “she was killed because she inadvertently got caught up in a complex political power struggle in a violent city famed for its rioting and brutality, and in which murder was the order of the day.”

There are further reasons to believe that the contemporary tale about Hypatia is false.

Our best contemporary source about her – Socrates Scholasticus – was a Christian, and he praised her as a great philosopher; some of her admiring students were Christians and went on to become bishops; scholarly inquiry continued in Alexandria after Hypatia’s death.

Likewise, calling Giordano Bruno a “scientist” is misleading at best. He was deeply committed to the supernatural; his views on astronomy would get him kicked out of any university today. He thought that planets spun on their axes and orbited stars because they enjoyed the change in temperature while doing so. Nothing Bruno did was remotely scientific, even by sixteenth-century standards.

So why was he killed?

Bruno’s Wikipedia page says that he was “tried for heresy by the Roman Inquisition on charges of denial of several core Catholic doctrines,” but the source for this claim seems to be a blog post from 1997.

An eccentric theist, Bruno thought that Jesus Christ was a magician, that the Trinity was nonsense, and that the Church was completely unnecessary. He was a hot head. Ultimately, though, we don’t know why he was killed. We don’t know the charges against him. The relevant documents have been lost.

“But William, you thick-skulled ignoramus!” I hear you yell, “everyone knows that Galileo was tortured because he proved that the sun was the centre of the solar system!”

My friend, Draper and White have fooled you.

There are many important details that get in the way of this good story. Galileo was a devout Catholic, firmly convinced of the divinity of Jesus Christ, the resurrection, and the virgin birth. He quoted Augustine and Jerome when defending his faith. He was supported by many cardinals and bishops; his critics were philosophers committed to the worldview of Aristotle. He didn’t have enough evidence to support his theory (heliocentrism wouldn’t be clearly supported by physical findings for another two centuries) and was never tortured or jailed. After his trial, he continued working, and published his treatise on motion, Two New Sciences, in 1638. In papal Rome, it sold out immediately.

I doubt these legends about the Church oppressing scientists will ever go away. Too many people depend on them. Some atheists like to state, in self-congratulation, that religion is distinctly irrational, and science is distinctly rational. This is the anti-historical, anti-philosophical, and confidently mulish view of science propagated by the New Atheists. The New Atheists did not simply fall into error: they jumped headlong into it. They were dogmatic and painfully unfamiliar with most of the topics they spoke about. They supported empiricism and “evidence,” and assumed that they were superior to others for this reason. Yet, they rarely made empirical arguments and their idea of “evidence” was an extremely narrow one. Their attitude towards philosophy and history was dilettantish. When any of their opponents – even atheists – tried to introduce some nuance or context, they dismissed those critics as “relativists” or “apologists.” There’s no need to make a detailed historical argument when you can just yell “Galileo,” conjure assent, and sell a million books.

As Tom Holland (the historian) might note, their language of bringing the light of truth to people in the darkness of ignorance comes straight from the Gospel of John. “Science,” Mr Holland writes in his great book Dominion, “precisely because it was cast as religion’s doppelgänger, inevitably bore the ghostly stamp of Europe’s Christian past.” When atheists claim that the Catholic Church set humanity back a thousand years, keeping Europe chained to fables and superstitions, they don’t sound like historians. They sound like Protestants.

The idea that “science” is entirely dispassionate, depending only on experiments and reason, is hard to sustain. Like any human endeavour, science is a complex, messy, emotional process. No one can even make an observation without a huge, pre-existing apparatus of theoretical assumptions. Modern science is so technical and complicated that it’s impossible for anyone except a specialist to follow the intellectual paths that lead to a scientific conclusion. Even scientists in one field rely on experts in another: science depends on arguments from authority no less than religion does.

How does the replication crisis affect the prestige of science? When research depends on government and industry funding, is it less or more likely that scientific results will please these benefactors? When promotions and pay rises depend on gratifying powerful organisations, is it less or more likely that scientific results will reflect the assumptions of those in power? When scientists come up with different conclusions, do they politely discuss them over a cup of tea? No – often, they hector, blacklist, and ignore each other. (See the arguments between the various schools of interpreting quantum mechanics.) The chemist August Kekulé discovered the ring structure of a benzene molecule. He was nowhere near a lab when he did so. So how did he do it? He had a dream about a snake eating its own tail. How poetic! The “scientific method” does not explain how people generate scientific explanations – and can anyone be free of personal prejudices when selecting and interpreting data?

There are some people who have fervent views about science which aren’t illuminated by any serious historical or ethical understanding, and sometimes claim that science can actually replace these forms of inquiry. This viewpoint – if it’s ever coherent – roughly says that technological progress is everything; that a flinty utilitarianism is the only consistent and impartial social philosophy; that free will is an illusion; and that, since only scientists and engineers are free from archaic and sentimental delusions, they ought to have a much larger say in what happens. These people will have you believe we should be worried about theocracy. What they propose is even scarier, because it’s more likely to occur.

You might consider the evil uses of technology – germ warfare, atomic bombs – but maybe even more frightening are “good” uses of technology: the methods of promoting efficiency and health might have alarming consequences.

You don’t need to read Frankenstein or watch Black Mirror to imagine them: the problems of unemployment caused by automation, a society in which people live for hundreds of years, rich parents and hired lab-coats developing programmes for genetically modified children. Should anyone automatically approve these advances? There is – or at least there should be – a fear that the excitement and prestige of the scientific process can undermine critics who ask how or whether to use certain innovations. The fear is that the momentum of scientific advance is impossible to stop. With a long history of ethical inquiry, the major religious traditions should question scientific and technological progress.

If Messrs Hutchings and Ungureanu were philosophers, they might have made a different argument against the Conflict Thesis, at least in its more modern forms. A common assumption is that a proper understanding of science will inevitably reveal that religious belief cannot be rationally justified, and that science has eliminated purpose and meaning from the universe. But the elimination of purpose and meaning is not a scientific “result” or “discovery” – it’s an interpretation of scientific discoveries, an unsupported philosophical worldview.

The New Atheists spruiked a philosophical viewpoint: materialism, a thesis that is rarely defined, let alone defended.

You occasionally find atheists who are honest enough to admit this. In his book The Last Word, the philosopher Thomas Nagel acknowledges that a “fear of religion” (you might call it theophobia) often underlies the work of atheist intellectuals:

“Rationalism has always had a more religious flavour than empiricism. Even without God, the idea of a natural sympathy between the deepest truths of nature and the deepest layers of the human mind, which can be exploited to allow gradual development of a truer and truer conception of reality, makes us more at home in the universe than is secularly comfortable. The thought that the relation between mind and the world is something fundamental makes many people in this day and age nervous. I believe this is one manifestation of a fear of religion which has large and often pernicious consequences for modern intellectual life.”

He continues:

“I speak from experience, being strongly subject to this fear myself: I want atheism to be true and am made uneasy by the fact that some of the most intelligent and well-informed people I know are religious believers. It isn’t just that I don’t believe in God and, naturally, hope that I’m right in my belief. It’s that I hope there is no God! I don’t want there to be a God; I don’t want the universe to be like that. My guess is that this cosmic authority problem is not a rare condition and that it is responsible for much of the scientism and reductionism of our time. One of the tendencies it supports is the ludicrous overuse of evolutionary biology to explain everything about human life, including everything about the human mind.”

The American philosopher John R. Searle puts it this way in his book Mind:

“Materialism is the view that the only reality that exists is material or physical reality… There is a sense in which materialism is the religion of our time… Like more traditional religions, it is accepted without question and it provides the framework within which other questions can be posed, addressed, and answered. The history of materialism is fascinating, because though the materialists are convinced, with a quasi-religious faith, that their view must be right, they never seem to be able to formulate a version of it that they are completely satisfied with and that can be generally accepted by other philosophers, even by other materialists.”

Reviewing a book by Carl Sagan, the evolutionary biologist Richard C. Lewontin wrote:

“Our willingness to accept scientific claims that are against common sense is the key to an understanding of the real struggle between science and the supernatural. We take the side of science in spite of the patent absurdity of some of its constructs, in spite of its failure to fulfill many of its extravagant promises of health and life, in spite of the tolerance of the scientific community for unsubstantiated just-so stories, because we have a prior commitment, a commitment to materialism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counter-intuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door.”

So materialism is assumed to be true and assumed to be the only acceptable worldview even though materialist philosophers themselves can’t give a coherent and satisfying argument for it. Is it any surprise, then, that many scientists throughout history have allowed the divine through the door?

Of Popes and Unicorns gives a list of scientists, past and present, who consider their research as a complement to their religion. I can add a small bit of personal experience here.

When I was a student in Cambridge, every day I walked past the entrance to the original Cavendish Laboratory site on Free School Lane. (Researchers from the Cavendish alone have won 30 Nobel prizes.) On the old oak doors is a quotation from Psalm 111: Magna opera Domini exquisita in omnes voluntates ejus. They were almost certainly carved at the urging of the first Cavendish Professor, James Clerk Maxwell.

The lab’s new building in West Cambridge, built in 1973, has the same passage in Myles Coverdale’s translation: “The works of the Lord are great; sought out of all them that have pleasure therein.”

In another article (https://www.experimental-history.com/)], Richard Smith, the former editor of the British Medical Journal, commented:

"It's fascinating to me that a process at the heart of science is faith not evidence based. Indeed, believing in peer review is less scientific than believing in God because we have lots of evidence that peer review doesn't work, whereas we lack evidence that God doesn't exist."

When I hear the term "trust the science" I hear a request to maintain the faith - a religious appeal, if you wish.