If you’re wise enough not to be on Twitter, you would have missed the controversy on that platform this week. Rightly proud to have completed a Ph.D. at Cambridge, Dr Ally Louks posted a photo of her thesis, “Olfactory Ethics: The Politics of Smell in Modern and Contemporary Prose.” You can find the abstract (written for specialists) online:

For whatever reason, Dr Louks’s tweet spawned a boorish mob: loud, braying imbeciles emerged from their dens, emitting rubbish about the unimportance of humanities research; mutants and miscreants dredged themselves up from their stagnant waters to spew bile about women ruining academia. Many rushed to defend Dr Louks, not that she needed it. Somehow throughout all this, she has conducted herself with grace and aplomb – two characteristically Cambridge virtues.

As someone who wrote a thesis for the same faculty at the same university, I would like to offer a few comments on the matter.

First of all, nobody calls our research stupid or pointless! Only we’re allowed to do that!

Furthermore, as you might expect, the most insightful commentary about this was on Substack. Amos Wollen pointed out that “Adjectives like ‘smelly’, ‘putrid’, and ‘foul-smelling’ aren’t morally neutral.” Ella Dorn wrote that people were angry about the Ph.D. “because its abstract reveals that it is literally just a vehicle for a series of sociopolitical truisms that are already the institutional status quo, and have been for over forty years. It comes off worse for the fact that the books she mentions are extremely widely-read and incredibly obvious - (Perfume? Really?) - and that the abstract cycles through a range of simplistic oppositions that work much better in pornography than they do in art or literature - housed/homeless, human/animal, black/white, young girl/old man, queer/unqueer.”

I agree with both points: I think that smell is an interesting topic to research, but I do find the English faculty talk of “power structures” a tad boring and reductive.1

The point (I think) that Dr Louks reveals is that “natural” reactions to physical phenomena are in fact always shaped by culture. This is true for smelling and also true for eating and drinking. There’s a lot to say about that, but as everyone knows, in the academy, you have to specialise, and my specialty is whisky.

The artistic and philosophical implications of whisky (and alcohol generally) are criminally understudied. This is surprising considering how many writers and philosophers are notoriously fond of a beverage. But maybe it’s not surprising, given our current situation. Any analysis about how we relate to the world must begin with our body, yet most of us live curiously disembodied lives: we sit in front a screen at work and sit in front of a screen at home. Most of us forget what all dancers, musicians, and athletes know: we think with our bodies. This is one reason why gyms, Pilates classes, and massage parlours have become so popular in recent years: to remind us that we connect to the world through our bodies.

When it comes to eating and drinking, we literally incorporate the material of the world, and this has a significant impact not only on our bodies but our minds. But in our fast, busy lives we obscure this connection. Eating a take-out burger is the nutritional equivalent of doomscrolling: it replaces the genuine links you have to the world. It makes you feel alienated, unfulfilled.2

By contrast, a good meal or a nice glass of whisky is overloaded with what Hartmut Rosa would call “resonance” – the transformative relationship between body, mind, and world that connects us to history, art, friendship, love, even God.

Shall I say it, reader? Whisky gives you cosy moments.

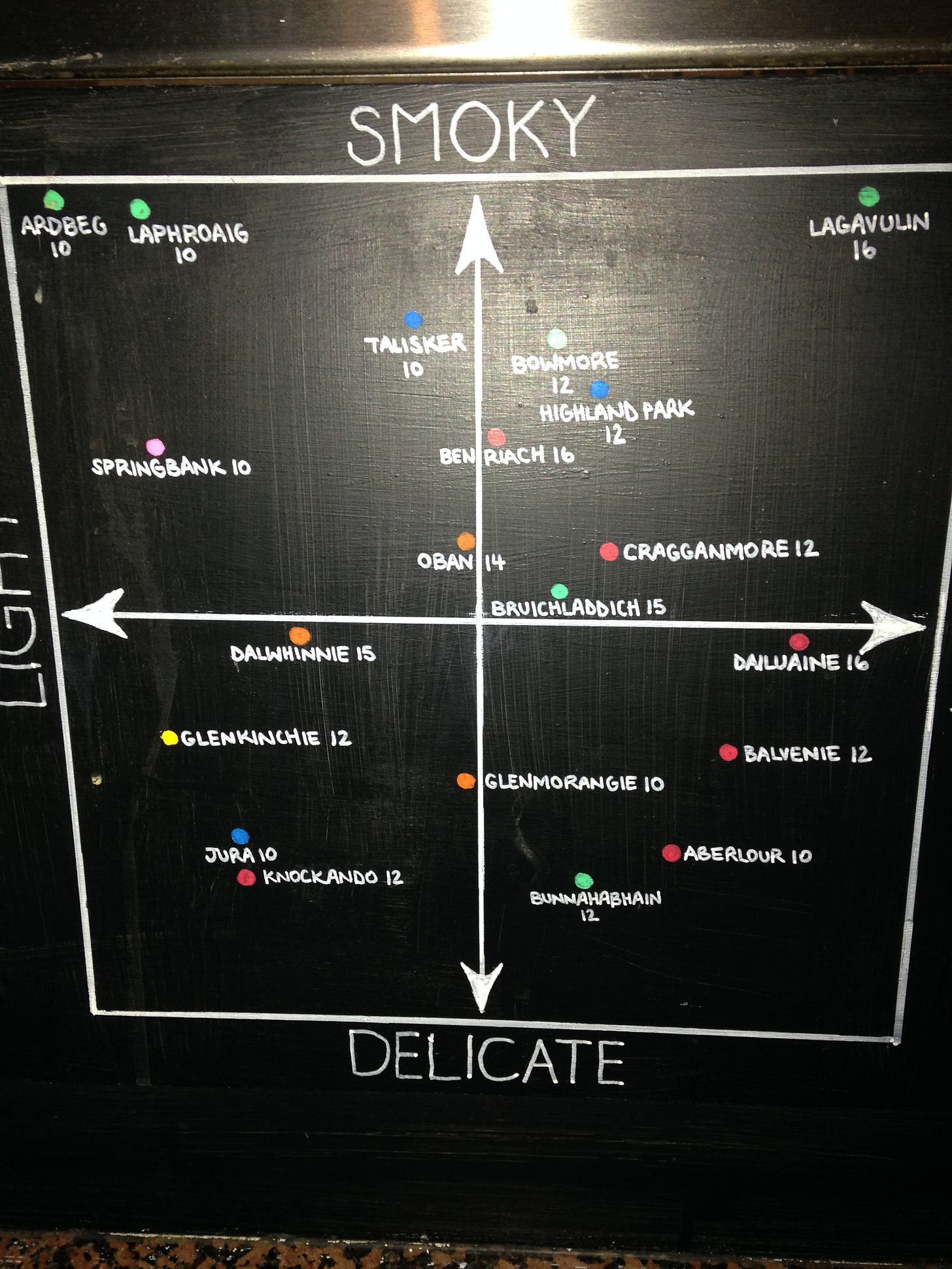

My relationship to whisky started when I was doing my research at Cambridge – there are not a few important people who would be upset to know that I spent all my scholarship money on alcohol. One December, the lads and I drove from Cambridge to Scotland. We parked the Ladmobile somewhere in Edinburgh and investigated the bibulous relationship between body, mind, and world. In a tavern, I came across this chart which is still an important tool in my research:

It’s the smokier whiskeys I prefer – the smokier the better. I want it to taste like a campfire. As someone who reads and writes for a living, I need this reminder that I am embodied; that the joys of the body are as valuable as the joys of the mind, and that they’re inseparable. That’s maybe another reason why I’m drawn to challenging, dissonant music: heavy metal, bebop, Schoenberg – because the greatest pleasures in life are never without a throb of pain: poetry, whisky, women.

Whisky is for adults. Boys like their craft beers and fruity ciders, and these are still good for light-hearted celebrations. But the man who has felt heartbreak or lost a job craves the vanilla smokiness of whisky. Beer accompanies bad, heartful renditions of “Mr Brightside.” The Scotch drinkers’ anthem is Steely Dan’s “Deacon Blues”:

Drink Scotch whiskey all night long

And die behind the wheel

They got a name for the winners in the world

I want a name when I lose

Whisky prepares you for the sorrows of life but is also a restorative with a mystical allure. A shot of Laphroaig can cure death, and even the scent of it is worth writing about. If Cambridge wants me back, I’m happy to return. I’ve already started the research.

I imagine the thesis itself is not as reductive as the abstract would suggest.

The best depictions of this are in the novels of Milan Kundera.

Have you read John D Burns? I think you’d enjoy 😏

The research sounds more interesting than its premises. I, like you, enjoy a Talisker, a Laphroaig, or a Bunahabhain, given the chance (and, coincidentally, am an old metal head). I like my whisky to smell peaty. But one might hesitate before approaching a person who smells the same, for reasons that are not entirely socially conditioned. Having spent quite some time with homeless people, I can say that some let off smells to which one would never wish to grow accustomed. I don't think even the most hardened Rousseauvian or blank-slate Maoist would imagine that one could raise a child to enjoy the smell of stale urine, dirty hair, dried up vomit or cheap liquor.

We gag as a reflex against poison. In most cases, when things smell bad, it is because they are bad for us. The exceptions do not, as the "queer theorists" suppose, undermine the rule. Or is my morning breath not bad, but just "different"?