“Religion has run out of justifications. Thanks to the telescope and the microscope, it no longer offers an explanation of anything important. Where once it used to be able, by its total command of a world-view, to prevent the emergence of rivals, it can now only impede and retard—or try to turn back—the measurable advances that we have made… Above all, we are in need of a renewed Enlightenment, which will base itself on the proposition that the proper study of mankind is man, and woman.” — Christopher Hitchens

You’ve heard the usual criticisms of major religious traditions:

Their texts don’t apply to us because they’re from a different historical period.

They’re riddled with contradictions.

They endorse repugnant beliefs and practices.

Conclusion? Ditch these outdated myths and embrace “liberal, secular, Enlightenment values”!

It’s a neat argument – if you’re content to sidestep history, ignore the nuances of religious thought, and avoid quoting any actual “Enlightenment” thinkers.

“Enlightenment” cheerleaders like Sam Harris, Steven Pinker, and the late Christopher Hitchens think its intellectual legacy is as consistent and recognisable as McDonald’s, a restaurant that provides the same nutritional value as their writing.

But as someone who has read a fair amount from the “Enlightenment,” I can tell you that its texts share the same vulnerabilities attributed to religious scriptures:

Their texts don’t apply to us because they’re from a different historical period.

They’re riddled with contradictions.

They endorse repugnant beliefs and practices.

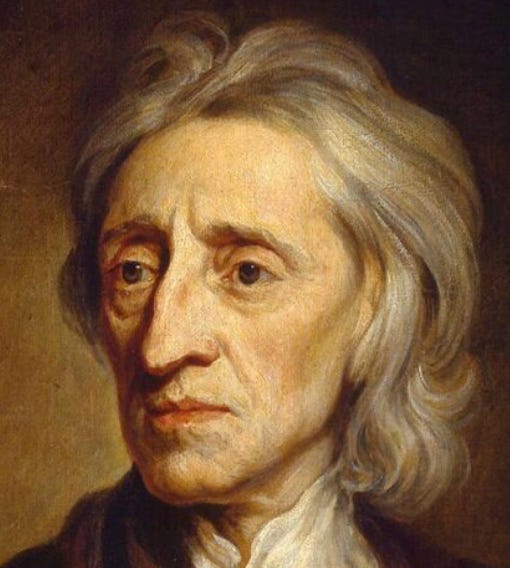

Despite the word “Enlightenment,” evoking brightness and clarity, trying to define it puts you into a fug. So, I’m not going to. Instead, I’m going to focus on only one author, and show how the typical criticisms of religious texts also apply to his work. My subject today is John Locke.

Why do I pick on him?

He’s widely considered one of the most important European philosophers of the seventeenth century. More than any other writer of the period, he clearly combined the principles we now take to be modern: individual rights, property rights, religious toleration, the belief that the legitimacy of a government needs the consent of its citizens. The United States of America is sometimes described as a Lockean experiment.

But anyone quoting Locke to defend “Enlightenment” ideals is as selective as the religious zealots they deride. The hornswoggling defenders of the “Enlightenment” tend to leave out that Locke used scriptural exegesis to support his political ideas, his language was full of references to the Old Testament, he had unclear views about slavery, he advised press-ganging beggars into military service, and he had views about minors that would make Miss Trunchbull cry out “Oh, won’t somebody please think of the children!”

Now, I am perfectly willing to concede that the Bible, an excellent stimulus of reflection and contemplation, is not a good source for specific guidance because no part of it was written with us in mind. But neither were the “Enlightenment” texts. They’re from a period of history which is also foreign and strange. There is a huge gap between Locke’s background – seventeenth-century Puritan and Scholastic – and ours, making any easy inferences impossible.

Born to Puritan parents and educated at Oxford, John Locke is described by his acolytes as the alarm bell that ended the dogmatic slumbers of the past. But lest you think that he was the incarnation of modern political thought, or a saviour sent back in time to drag a regressive society into the present, it’s important to note that he was almost always responsive to the problems of his age, one marked by turbulence and instability. Just as today’s undergrads pen cringe-worthy odes to lovers, so Locke extolled Oliver Cromwell and Charles II.1

Among his writings at university were poems written to celebrate the Restoration. The return of Charles would drive out anarchy and bring in peace:

So now in this our new creation when

This isle begins to be a world again,

You first dawn on our Chaos, with design

To give us order…

Till you upon us rode and made it day

We in disorder all and darkness lay.

A poem in praise of a king? How do Americans who claim Locke as a political ancestor react to this? Don’t know.

How would they react if they knew Locke and his Oxford colleagues also praised the rule of Oliver Cromwell? Don’t know.

Even in prose, Locke’s Oxford writings contradict the ideas he would later be known for: Two Tracts on Government (written in 1660 and 1662, but not published until 1967) were written in response to a fellow student, Edward Bagshaw, who rejected the state’s attempt to impose religious uniformity. In the preface to the first tract, Locke talks about how disruptive religious dissent has been and what his solution to it is: “for having always professed myself an enemy to the scribbling of this age and often accused the pens of Englishmen of as much guilt as their swords,” Locke claims, “there is no one can have a greater respect and veneration for authority than I.”

And it seems he’s right. Acknowledging the value of liberty, he maintains that a “general freedom” is a “general bondage,” and that only it would lead to “a liberty for contention, censure and persecution and turn us loose to the tyranny of a religious rage.”

In forming a Commonwealth, “it is yet the unalterable condition of society and government that every particular man must unavoidably part with this right to his liberty and entrust the magistrate with as full a power over all his actions as he himself hath…”

Locke’s argument – accepting the Restoration and King Charles’s later Act of Uniformity – is that religious dissent is less important than peace, that people ought to accept the religious policies of the reigning establishment. After all, “Christ commands obedience though it were burdensome.”

And really, what is more dangerous? A wise king or an ignorant mob?

Whence is most danger to be rationally feared, from ignorant or knowing heads? From an orderly council or a confused multitude? To whom are we most like to become a prey, to those whom the Scripture calls gods, or those whom knowing men have always found and therefore called beasts? Who knows but that since the multitude is always craving, never satisfied, that there can be nothing set over them which they will not always be reaching at and endeavouring to pull down…

Locke concedes that the magistrate has no power over the consciences of his subjects, only outward acceptance and subservience. Conscience itself comes from God:

God implanted the light of nature in our hearts and willed that there should be an inner legislator (in effect) constantly present in us whose edicts it should not be lawful for us to transgress even a nail’s breadth.

There’s a blatant contradiction within the one tract: if people must violate their consciences to follow the law, they distance themselves from their God; if they defy the law to stay true to their conscience, they challenge the authority of the ruler and the civil structure designed to maintain national peace.

Locke’s Oxford writings reveal political pragmatism rather than philosophical consistency. Far from being juvenile vacillation, these shifts demonstrate Locke’s concern with the political stability of his time. It’s this sensitivity to the political crises of his era that shaped his ideas about governance, liberty, and consent – concepts that remain crucial to modern debates within political philosophy. But ideas don’t emerge in a vacuum. Many “Enlightenment” thinkers were not disinterested idealists. They were not brains in vats but products of an unstable, antagonistic environment, fighting for relevance and distinction.

Maybe we’ll find more consistency if we examine Locke’s views of slavery – absolute or arbitrary power over another. After all, the abolition of slavery is seen as one of the great triumphs of the “Enlightenment,” even though it was mass movement only among dissenting Protestant Britons and didn’t occur in the United States – supposedly founded on “Enlightenment” ideals – until 1865.

Locke is famous for a type of political liberalism which prioritises rights and consent. This fits nicely with arguments against slavery, but Locke accepted that unjust aggressors defeated in war could legitimately be enslaved.

There are, in fact, quite a few Locke scholars arguing that he intended to justify the institution and practice of New World slavery. I don’t think he did, but his views on the topic are unclear, and the scholarly debate about it continues.

Locke served as the personal secretary to the merchant adventurer and Lord Proprietor of Carolina, Anthony Ashley Cooper, later the Earl of Shaftesbury. Locke also served as secretary to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina (from 1671 to 1675) and the Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations (from 1673 to 1674). He and Shaftesbury received shares in the Royal African Company which they sold for profit a few years later. (Though, Holly Brewer notes, this was payment from King Charles II, who was so broke he stopped Crown payments and paid Locke and Shaftesbury in Royal African Company stock.)

As Shaftesbury’s clerk, Locke would have read plenty of information regarding slavery in the New World. He contributed to and revised the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina. One colonial instruction reads “Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his Negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever." Locke didn’t write this. But he didn’t decry it or remove it.

His arguments against slavery were written in response to Sir Robert Filmer’s defence of absolute monarchy; in the Second Treatise of Government, Locke wrote that under James II England was on “very brink of slavery and ruin.” Locke opposed the principle that kings inherited not only land but also “rule and power” over its inhabitants. This, Locke contended, is what turned a nation into slaves. James Farr argues that, since Locke never explicitly links his just war aggressor theory to Africa or America, the philosopher’s opposition to slavery applies “in the context of Whig resistance to Stuart absolutism.” Locke’s aversion to “slavery” was aversion to English absolute monarchs, and his involvement with colonial trade and government is enough to impugn his status as the great defender of liberty and individual rights.

Unlike many other writers of his age, Locke didn’t appeal to the scientific language of “species” to explain racial differences. As a Christian, he believed there was a single race of humans that descended from Adam. But this puzzles commentators.

How, then, did he justify his colonial activities when his theoretical writings contradict the principles of slavery in the New World? Don’t know.

Let’s have a closer look at his aggressor theory from the Second Treatise of Government:

captives taken in a just war, are by the right of nature subjected to the absolute dominion and arbitrary power of their masters. These men having, as I say, forfeited their lives, and with it their liberties, and lost their estates; and being in the state of slavery, not capable of any property, cannot in that state be considered as any part of civil society. (My emphasis)

On this view, since an unjust aggressor has forfeited his right to life, he can’t complain if he suffers some slighter punishment than death. He’s not a part of “civil society” and has forfeited the legal protections of it. A defender of U.S. foreign policy, then, can use Lockean arguments to justify the indefinite detention and “enhanced interrogation” of “terrorists.” Maybe this how the United States of America preserves the values of the “Enlightenment”!

Here is Locke, often heralded as the architect of individual rights, the man who lent his talents to the bureaucracy of colonial oppression. The “Enlightenment,” that grand project of human emancipation, was often inseparable from the sordid realities of exploitation and conquest. Locke is the great champion of property rights. “Enlightenment” arguments for property holding are deeply connected to liberty. Slaves were considered property, bought and sold like things.

How, then, do we preserve the sanctity of “Enlightenment” thought? Must we mute the self-congratulatory praises of its cheerleaders?

Anyone appealing to the Enlightenment must wrestle with this. So, when Matt Johnson claims that you can draw a straight line between Enlightenment and today’s freedoms, I react with sour incredulity. You can’t even draw a straight line between John Locke and John Locke!

Locke developed much of his political thought in an attempt to defend the majority against the “inconveniences” of an aggressive minority, and, as mentioned above, considered that legitimate government depends on the consent of those governed. This assumes that an individual person is more fundamental than the society or community. Many political thinkers don’t smell what the Locke is cooking. They argue you can’t define people without their social and political ties: the bonds of nationality and culture – and the obligations they carry – exist before individual choice and are essential to defining any group as a political unit. No civil society, no “individuals.”

So how do the Enlightenment all-stars defend their individualistic assumption? Don’t know.

In any case, Locke’s argument that government ought to be consensual raises wonderful problems: how continual must this consent be? Are people born after the foundation of a civil society bound to obey its laws, when they weren’t a part of the original agreement?

Here, Locke makes a distinction between express and tacit consent. Express consent (such as swearing an oath) binds a person to the laws of a civil society forever. But if a state respects citizens’ rights – including the right to emigrate – and someone continues to enjoy its protections and privileges, that person has tacitly consented to it. If they ever change their mind, they’re free to go somewhere else.2

But this hardly deserves the label “consent,” and it’s not clear this creates the sort of obligation that Locke wants it to. As E.J. Lowe points out political obligation doesn’t typically depend on consent as much as co-operation between members of a community. It was in fact another “Enlightenment” writer, David Hume, who rejected social contract theory, especially Locke’s version of it. After arguing that most governments didn’t originate from any agreement with citizens, Hume contended that they hold power not through mythical contracts but because they provide the essentials: order, security, and justice. People obey the laws because it's useful to, not because they signed up to anything.

Besides this theoretical concern, there’s a practical one. How fair or realistic is it to expect people to move and start a life elsewhere? Hume again:

Can we seriously say, that a poor peasant or artisan has a free choice to leave his country, when he knows no foreign language or manners, and lives, from day to day, by the small wages which he acquires? We may as well assert that a man, by remaining in a vessel, freely consents to the dominion of the master…

Locke’s notion of tacit consent – that citizens consent to government simply by living within its borders and enjoying its protections – is deeply flawed. As Hume astutely points out, this so-called "consent" is not freely given; for most people, the idea of leaving their country and starting anew is only a dream. Locke’s notion of tacit consent is a convenient fiction, and his society is a bit like Hotel California: you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.

If consent is the foundation of legitimate government, and most citizens are not truly free to withhold it, then on what basis can Locke’s theory claim to uphold individual liberty? Don’t know.

So how, exactly, is this a substantial improvement over the coercive monarchies Locke opposed? Don’t know.

How is this “Enlightenment” figure meant to guide us in contemporary debates about political consent and legitimacy? Don’t know.

There are further problems. If, on Locke’s view, governments are formed to protect the rights of the people, what happens when there’s a dispute between the people and the government? What happens if those meant to administer justice end up inflicting violence and injury?

… war is made upon the sufferers, who having no appeal on earth to right them, they are left to the only remedy in such cases, an appeal to heaven.

Dammit, John! You’re meant to be an Enlightened intellectual! Don’t mention Heaven!

Even if today’s members of Team Enlightenment accept social contract theory, they must notice that the right to vote has no part in Locke’s notion of consent and obligation. He doesn’t even imply that the governed have a right to participate in government (which is actually a pre- and post-Enlightenment idea.) Locke was writing when only male property owners could vote in parliamentary elections, and he didn’t challenge this restriction. Other writers of the period did favour more expansive views of democracy, but if Team Enlightenment is going to reject the Bible completely because its historical context seems unjust by our standards, they must do the same with John Locke. Or, if they’re going to be selective about which “Enlightenment” works represent contemporary freedoms, they can’t scold believers for doing the same with Bible verses, some of which are, admittedly, quite nasty.

But so too are some works from the “Enlightenment.” Locke’s “Essay on the Poor Law” advocates hard labour and whipping for those “idle vagabonds” who “pretend they cannot get work.” Locke extends his enlightened perspective to children:

… if any boy or girl, under fourteen years of age, shall be found begging out of the parish where they dwell (if within five miles’ distance of the said parish), they shall be sent to the next working school, there to be soundly whipped and kept at work till evening, so that they may be dismissed time enough to get to their place of abode that night… (My emphasis)

Since the campaigns to end mistreatment of children and the campaigns to extend the franchise became significantly stronger in the nineteenth century, I don’t see why journalists aren’t calling for a return to Victorian values.

I’m sure that’s not the only view of Locke’s that makes Team Enlightenment squirm. Famously, Locke’s views concerning religious toleration don’t extend to Catholics (potentially seditious) or atheists (can’t be trusted to keep oaths):

… those are not at all to be tolerated who deny the being of a God. Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist. The taking away of God, though but even in thought, dissolves all…

Locke isn’t being hypocritical, as many have suggested. He thought that theism was not only a matter of faith but also reason; he thought there were rational proofs for morality and for the existence of God. In other words, he thought atheism was irrational. Although an atheist might respect a contract, in Locke’s view he can have no rational justifications for doing so. Locke’s concern is not that an atheist might break one particular contract, but that atheism is inherently corrosive of the whole moral and social order. This might be a shock for the “Enlightenment” toadies, who continually claim that “Enlightenment” philosophers used reason to confirm the intellectual superiority of atheism.

Nothing I’ve said will surprise a scholar of Locke or anyone who has actually studied intellectual history. In fact, much of this is common knowledge. But the members of Team Enlightenment and their internet progeny are neither historians nor philosophers. They write glib diatribes for the departure lounge. They’re airport atheists. Even though Locke remains hugely popular, his work inspiring libraries of interpretations and commentaries, hardly anyone today mentions his book The Reasonableness of Christianity because people are influenced by their culture even in interpreting the past, and the prevailing culture among talking heads is one that treats religion and reason as antithetical. As one learns in literary studies, all reading contains an element of subjectivity. “Immaculate perception” is impossible.

In their zeal, the airport atheists reduce religion to a litany of violent anecdotes and the “Enlightenment” to a parade of secular heroes. In opposing religion and “the Enlightenment” – without bothering to define either word – they ignore thinkers like Locke and his belief that Christianity and reason were deeply intertwined. This selective reading mirrors the very simplifications they accuse religious people of making.

Maybe “selective reading” is too generous. Sam Harris’s shallow tirade The End of Faith opposes “religion” and “reason” (what is “reason” for Mr Harris? Don’t know) but mentions Locke only once, in a footnote saying that Pope Pius X apparently proscribed the “Essay on Human Understanding.” (Locke’s work is actually called An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, but whatever. Who needs accuracy when you have reason?)3 Steven Pinker’s cute book Enlightenment Now mentions Locke twice: once to say that Locke “reconceptualised” childhood (clearly Mr Pinker hasn’t read “Essay on the Poor Law”) and again to say that Locke thought human equality was a “self-evident truth,” (clearly Mr Pinker hasn’t actually read anything Locke wrote.) Christopher Hitchens’s bloated whinge God is Not Great doesn’t mention Locke at all, and its last chapter, entitled “The Need For A New Enlightenment,” doesn’t quote a single “Enlightenment” figure.

Unsurprisingly, Locke’s writings were frequently revised, are inconsistent, and don’t supply any easy answers for the problems we have today. We shouldn’t reject him entirely or accept him uncritically. Maybe the most “Enlightened” thing to do is to is to read bygone thinkers with care. Just as religious texts must be read in their historical and liturgical contexts, so too should we read “Enlightenment” thinkers with an awareness of their limitations, contradictions, and historical baggage. This, hopefully, would end the constant piffle about how a handful of wigged men from centuries ago will save the world with their moral poise and intellectual acumen.

If you want to appropriate the legacy of the Enlightenment – or even hitch a ride on the coattails of one of its luminaries – you have some tough thinking to do. You can’t just take it as if it’s a neatly tied package of virtue and progress. The contradictions are too stubborn, too knotted. If you congratulate yourself for your scepticism, you must treat the “Enlightenment” with more than blind admiration and sentimentality. You need a sharp, uncompromising eye.

But, as a poor, dumb, Christian, I am unable to deal with inconsistency and only believe what people tell me to. So which arguments best represent “Enlightenment” values, and why? Will the real John Locke please stand up?

He later praised the rule of Mary II and William III of Orange.

Maybe you could use Lockean arguments to say that Locke himself “tacitly” consented to slavery in America.

Yes, I know the printed title was An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding.

“but if Team Enlightenment is going to reject the Bible completely because its historical context seems unjust by our standards, they must do the same with John Locke. Or, if they’re going to be selective about which “Enlightenment” works represent contemporary freedoms, they can’t scold believers for doing the same with Bible verses, some of which are, admittedly, quite nasty”

I think this would be a fair critique if not for the underlying premise that religious texts like the Bible are the literal words of an infallible God. This seems to make rejecting parts of it and accepting others more problematic than doing the same for works written by forward thinking but still fallible humans, no?

"Their texts don’t apply to us because they’re from a different historical period.

They’re riddled with contradictions.

They endorse repugnant beliefs and practices."

This is a strawman, athiests don't believe that religious texts should be discarded because they aren't from the modern age or contain contradictions. Rather, the basis of their claims rest in superstituion and faith, rather than reason. Anyone of any religion can read the words of Locke, critique it, subject it to reason, and adopt its statements based on that person's own reason. The same can't be said for religious texts, which requires that reader accept superstitution based on faith, rather than reason.